- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

|

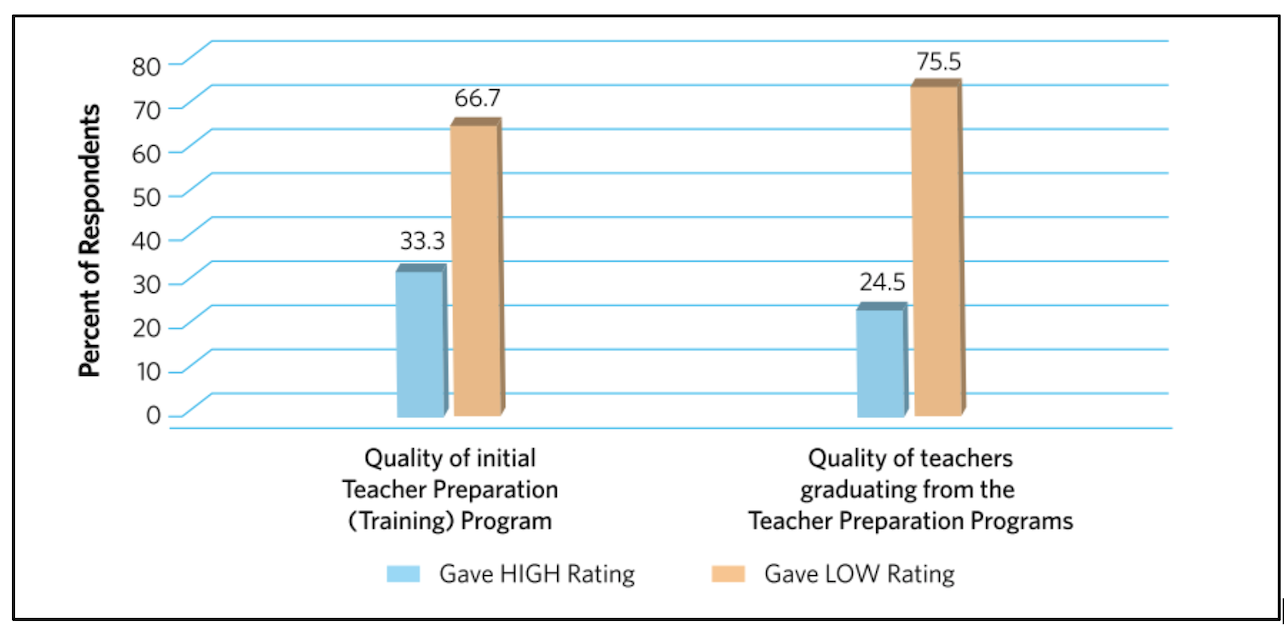

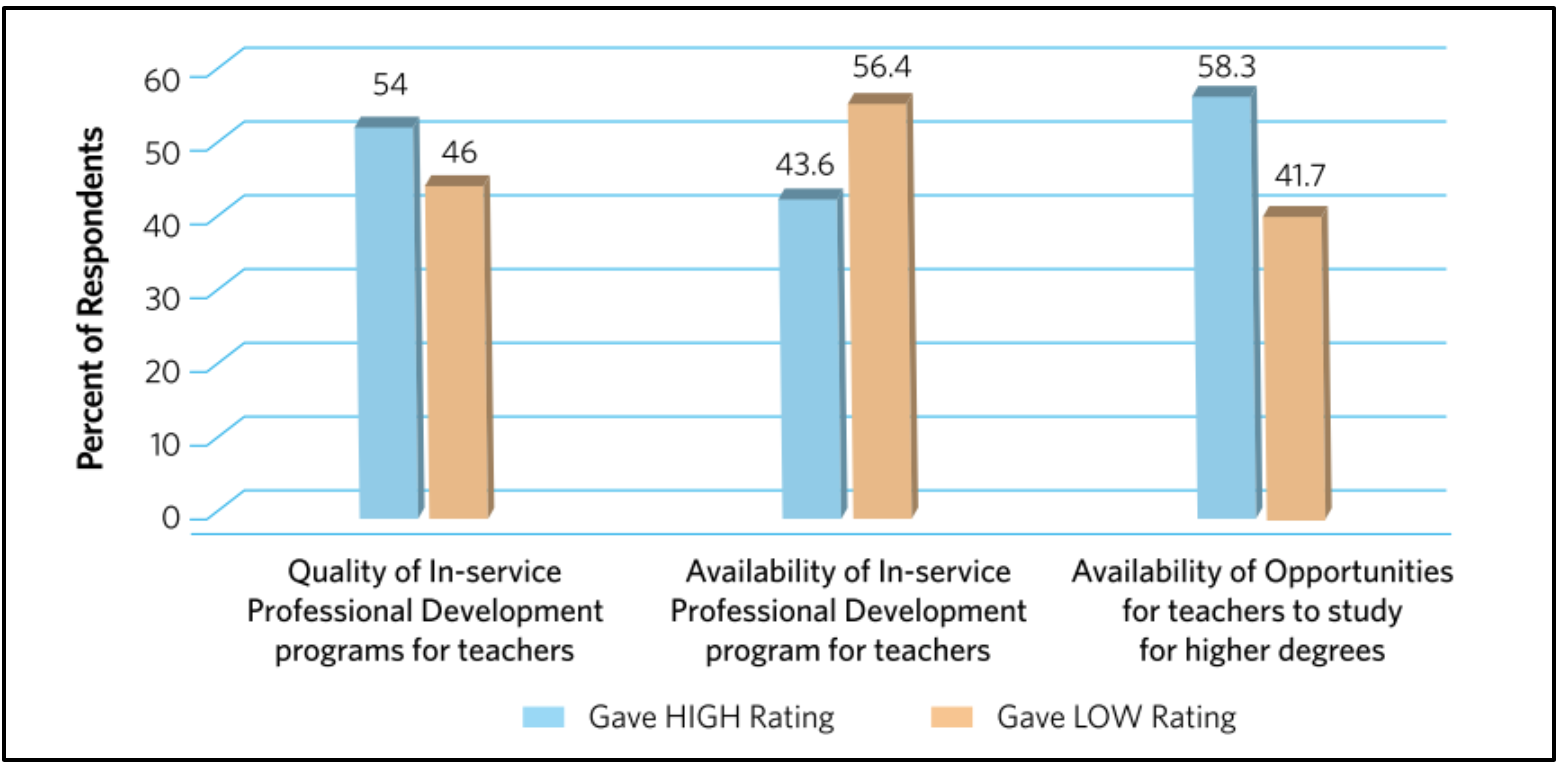

Abstract Teacher Professional Development (PD) attracts a high level of interest today from educators and scholars around the world who wish to better understand this practice. This is due to the results from a broad range of research in the past decade that show a link between teacher practice and student achievement as well as the significance of teacher practice in education reform. This practice may take different forms: it can be either formal or informal and can be conducted in a range of settings either inside or outside of school. There is no single way to design and provide this practice; each nation implements teacher PD according to its own circumstances. This article aims to compare teacher PD practices in Kuwait and Singapore in order to highlight the relative absence of this practice in Kuwait and to take lessons from one of the examples of best practices in the world – Singapore – in how Kuwait can design and develop good PD for its teachers that will help in raising teacher quality in Kuwait. This research used a comparative analysis to highlight the differences between these two cases and concludes with a number of fundamental principles in designing and providing teacher PD practice that may help Kuwait in developing this practice. Using a qualitative approach, data was collected by reviewing and analysing primary and secondary documents relating to the two countries under examination. The findings of this research indicate the absence of formal teacher PD in Kuwait. The article calls for serious and urgent action from the Ministry of Education in Kuwait to guarantee that its teachers are of high quality by recommending that the country follow the fundamental principles identified in Singapore’s practice. Keywords: Teacher Professional Development, In-service Training, Teacher Training, Kuwait, Singapore. 1. Introduction: Nations around the world are increasingly interested in improving teacher performance in the classroom and the path that they are increasingly following is to improve teacher knowledge and skills. This is what makes teacher professional development (PD) appear at the top of the educational agenda (Bubb and Earley, 2007). Teacher PD is one of the main topics that has attracted increased attention from educators and scholars in order to explore best practice that will increase teacher performance and school standards. In any organisation people are the main resource and to achieve better results from these people they need appropriate professional development. This article aims to compare teacher PD practices in Kuwait and Singapore in order to highlight the absence of this practice in Kuwait and to take lessons from one of the examples of best practices in the world – Singapore – in how Kuwait can develop and design good PD for its teachers that will aid in raising teacher quality in Kuwait. Building upon resent research, Alasfour (2017) conducted a comparative analysis on teacher preparation programs, “Teacher preparation programs in Kuwait: A profile comparative analysis”. The article aims to examine the initial teacher training in Kuwait and the lack of the programme’s quality in preparing the teacher. In this article my focus is on the in-service training in Kuwait, aiming to fill a gap in the literature and to complete an entire understanding of teacher training in Kuwait by examining in-service training in order to complement this previous work on pre-service training. There are several objectives by which to compare countries and conduct comparative research. One of these objectives is contextual description, which allows the researcher to know what other countries are doing in specific fields. Studying and comparing foreign countries and cultures provides the researcher with highly detailed descriptions. Moreover, as Landman (2008) states The comparison to the researcher’s own country is either implicit or explicit, and the goal of contextual description is either more knowledge about the nation studied, more knowledge about one’s own political system, or both. (2008, p. 5) Accordingly, looking in depth to Singapore’s teacher PD practice helps us to gain more knowledge in terms of designing and providing this practice. Moreover, Morgan (2016) argues that often countries that are lacking in specific educational practices can still provide valuable data; researchers can make good points when comparing one country with another even where these countries vary greatly. Comparing these practices helps others to improve their own practice by implementing some common principles shown in the cases under examination. 2. Background and Literature Review: Scholars use different terms when they define this practice, such as continuing professional development (CPD), teacher development, in-service education and training (INSET), staff development, career development, human resource development, and professional development (PD) (Bolam and McMahon, 2004; Hardy, 2012). These terms are defined differently by different scholars. However, when we review these definitions we see they have the same aims which make them almost identical. Bubb and Earley (2010) define teacher PD as a lifelong process. It may take place as formal or informal experience and this process includes other school staff as well as teachers. This process aims to improve working performance by enhancing the knowledge and skills of school staff and, as a result of this process, student learning and well-being are also enhanced. In their view, PD is an on-going process encompassing all formal and informal learning experiences that enable all staff in schools, individually and with others, to think about what they are doing, enhance their knowledge and skills and improve ways of working so that pupil learning and well-being are enhanced as a result. It should achieve a balance between individual, group, school and national needs; encourage a commitment to professional and personal growth; and increase resilience, self-confidence, job satisfaction and enthusiasm for working with children and colleagues. (p. 1) According to this definition, we can view teacher PD as a process rather than an event or activity that happens just once. It is a lifelong learning practice which teachers need to participate in as long as they are professionally active. This process may take different forms such as being formal or informal, individual or working with others. The main point on which the definitions agree is that through PD teachers learn how to perform better in the classroom, which will make students learn better. A number of scholars have found a correlation between teacher practice and student achievement, as well as a link with school change and reform. Villegas-Reimers (2003) states that successful teacher PD has a positive impact on student learning as this practice has a significant “impact on teachers’ beliefs and behaviors” (p. 20). Through PD teachers expand their knowledge and skills, which will improve teacher performance. This enhancement of their practice will increase student achievement (Speck and Knipe, 2005; Darling-Hammond et al., 2009; Yoon et al., 2007; Murray, 2014). Moreover, the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) by the OECD (2014) reported that most teachers who participated in the survey (91%) indicated that their PD has had a positive impact on their teaching performance. Furthermore, the impact of PD is not just on student achievement: PD activities can “change people’s lives and careers” (Bubb and Earley, 2010, p. 5). Furthermore, PD has an impact on teachers’ personal and interpersonal capacity and will increase well-being in the school environment (Bubb and Earley, 2010; Earley and Porritt, 2009). These significant effects illustrate why countries need to pay increased attention to teacher PD and improve their PD practice. 3. Teacher Professional Development Status in Kuwait As mentioned at the beginning, our aims in this article are to highlight the absence of teacher PD in Kuwait and to demonstrate how Kuwait can learn from others in order to improve its practice through clarifying a number of fundamental principles in designing and providing teacher PD practice derived from examining other best practice countries in teacher PD. We hope these principles may help Kuwait to improve its PD practice. In order to achieve this aim, it will be helpful to examine the current status of teacher PD in Kuwait and identify the particular factors which are missing in providing this practice. Unfortunately, there are significant limitations in the literature examining teacher PD practice in Kuwait. There is also no access to the policy documents that are set by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Kuwait. In view of these limitations, we have reviewed what is available in order to determine the status of teacher PD in Kuwait. These sources are as follows: a report by the Kuwait Ministry of Education (2014) titled National Review of Education for All by 2015, A Diagnostic Study of Education in Kuwait by the National Institute of Education (NIE) in Singapore (2013), and Alhouti & Male (2017) which explores the leadership preparation and development programme from the perspective of Kuwaiti school principals. The majority of teachers (95%) in primary and intermediate schools have a bachelor’s certificate in education (MOE, 2014). However, various reports show that they have not been trained well for their job (MOE, 2014; NIE, 2013). The yearly amount spent on training and development activities is 400,000 KD, equivalent to 800,000 GBP for all MOE employees, both teaching and non-teaching staff (MOE, 2014). Dividing this amount by the number of the employees (123,124) we find that the training budget per capita is 6.5 GBP annually, a sum generally acknowledged to be insufficient. The diagnostic study by the Singaporean NIE (2013) found that initial teacher training as well as in-service training is lacking and that teachers are not given equal opportunities to participate in these programmes. The majority of Kuwait MOE officers (66.7%) gave low ratings for the quality of Kuwait's teacher preparation programmes and 75.5% of them rated the quality of teachers graduating from these programmes as low. Moreover, 46% of Kuwait’s MOE officers rated the quality of in-service programmes as low, “which means that the lower quality teachers who graduate from pre-service training will not be able to look forward to quality in-service training as a remedy”. In addition, 56.4% of Kuwaiti MOE officers indicate that in-service professional development was not available for teachers. Figure 1 and 2 illustrate these findings. Figure 1: MOE Officers’ Ratings of Teacher Preparation Programmes Figure 2: MOE Officers’ Ratings of In-service Professional Development Programmes for Teachers These results illustrate the lack of teacher PD in Kuwait. This is why improving teacher PD practice in Kuwait is an urgent issue. What is significant in these results is that although the diagnostic study presents the opinions of Kuwaiti MOE officers, demonstrating that they are not happy with the current situation, it is they who have the authority to improve the situation.

Recent research has been carried out looking at the leadership capability of school principals in Kuwaiti public schools. This research interviewed ten intermediate school leaders in order to find out how they were trained and prepared for the position. The results of the study show that school principals are not happy with the PD currently available due to the absence of formal training programmes (Alhouti & Male, 2017). As there is not enough information about how teachers are trained, we refer to this research to present some of the school principals’ opinions about their PD programmes. We can assume that teacher PD is similar to the PD provided for principals as the MOE is the only provider of this training and have the responsibility in managing and designing the practice. When the researchers asked the principals to describe and evaluate the current status of their PD the majority of them were not satisfied. One of the respondents claimed “most courses focus on the theoretical aspect of leadership and abandon the real practical aspect. I attended 12 courses, none of which touched the reality” (Alhouti & Male, 2017, p. 44). Moreover, another participant stated, “[t]he specified time period for each training session period is very limited, you cannot prepare school leaders in this simple period” (ibid.). An interesting claim arose from one participant explaining the poor nature of the PD activities that he has participated in throughout his career. He commented: All the developmental courses available are useless. They are like the preparation courses we attended when we assumed the position. I am sure that I will not get any benefit from this course. So, I am not motivated to attend the course and I try to escape it to spare my time and reason from the silly things that I hear in such courses. The courses are only killing time. The mere names of the courses suggest the vapid and trivial contents. For example, there was a course for assistant school principals under the title ‘Know your personality through your signature’. Furthermore, while the title of a course may be accurate, such as ‘strategic planning’ the disaster is that the duration of such a course is only one hour. Who in the world can train leaders in strategic planning in just one hour?! (p. 45) This revision shows that PD practice in Kuwait is below the level of expectation of Kuwaiti MOE officers as well as that of school leaders with regards to their PD programme. If the MOE in Kuwait do not provide school leaders with PD practice of sufficient quality, we can assume that teachers in Kuwait are facing similar issues in their PD practice. Understanding the reasons behind this lack in PD practice for school staff in Kuwait may call for future research to highlight and identify this practice in more detail. 4. Teacher Professional Development in Singapore The reason for choosing Singapore to compare with Kuwait’s teacher PD practice is not only that Singapore ranked top of all international assessments in 2015 (TIMMS, PIRLS and PISA) and is known as one of the best education systems worldwide. Rather, according to TALIS research conducted by the OECD in 2013 focusing on lower secondary school teachers – the biggest international teacher survey – teachers in Singapore have the highest percentage (98%) across all participating countries (34 countries and sub-national territories) of teachers who undertook some PD activities in the twelve months prior to the survey. This survey offers significant information with regards to teachers’ autonomy, network, and knowledge (OECD, 2014). This demonstrates that Singapore is a good case to learn from in regards providing teacher PD. The Ministry of Education (MOE) in Singapore and the National Institute of Education (NIE) at Nanyang Technological University – the only teacher training college – as well as the Academy of Singapore Teachers (AST) are the bodies responsible for teacher PD for Singapore’s teachers. The three work very closely with each other and with the schools in order to identify their needs and design PD programmes (Jensen et al., 2016; NIE, 2009). Each year a senior manager – principal, vice principle, or head of department – discusses and plans with each teacher their yearly PD agenda in response to their interests and school’s needs as well as the requirements of the curriculum. This agenda then needs to be approved by the teacher reporting officer who is usually linked with the MOE (MOE, 2006; Bautista et al., 2015). The MOE provides 100 hours of training per teacher per year; most of these hours are scheduled during working hours. Undertaking these hours is optional; although teachers are not obliged to participate most teachers do so (Bautista et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2016; OECD, 2011). The aim is to offer teachers the learning opportunities that meet their needs according to their personal motivation and goals (Bautista et al., 2015). This means that the system is highly centralized by the MOE and this type of learning is not compulsory; however, teachers are self-motivated to participate in some type of learning activity. What may explain the high percentage of Singapore’s teachers participating in teacher PD activities is that teachers spend on average only seventeen hours teaching weekly, which is much lower than other countries according to TALIS 2013 (OECD, 2014). With regards to supporting teachers in PD, the MOE sponsors all teacher PD programmes. In 2006 it announced 250 million USD to ensure teacher PD for the next three years (MOE, 2006), a sum equivalent to 189.3 million GBP. Additionally, teachers who have at least six years of service can take half-pay leave for one month to give them time to undertake purposeful PD, to recharge and renew their skills, and those who have at least twelve years of experience can take up to two-and-a-half months of full-pay leave. Moreover, Singaporean teachers can claim between £300 to £500 per year for any learning experience that they choose, such as subscriptions to journals, membership of professional societies, and the purchase of computers and IT accessories (ibid.). 5. Conclusion The aim of this article was to compare teacher PD in Kuwait and Singapore in order to highlight the absence of this practice in Kuwait as well to identify the principles in the design and provision of teacher PD in Singapore. The MOE in Kuwait needs to consider these principles in order to better design and develop its own teacher PD practice. We can argue after this comparison study that formal teacher PD is absent in Kuwait and that Kuwait needs to take serious and urgent action to guarantee that its teachers are of high quality. It is important to clarify that we are not aiming to borrow the policies or practices that we examined in Singapore in order to implement them in the context of Kuwait. Rather, we are stating a number of general principles that we identified from investigating teacher PD in Singapore. The first principle learned from conducting this research is that teachers need to be part of the design process and involving teachers may help in designing a practice that fits their needs. As we found from this study, each teacher has their own needs as well as their own learning style. In order to gain benefit from PD, these activities need to match the teacher’s needs. The voice of teachers needs to be listened to when designing this practice. In this way, teachers will feel that this practice is designed for them, and that they have been part of designing it, which may increase their motivation in undertaking these activities. Secondly, this practice needs to be a long-term practice, and it be acknowledged as a lifelong learning process that should be available to teachers as long as they are in the teaching profession. This practice does not work as a one-off event or a short workshop. Teacher PD practice needs to be designed to be cumulative and connect activities and processes with each other. This research shows us that the more support that countries offer for the practice, the more successful it will be. Support needs to take the form of offering time to help teachers undertake these activities and tailoring this practice to be part of teachers’ working time, as well as offering appropriate amounts to cover the total cost of these activities. The amount that the Kuwait MOE spends on PD activities for all MOE staff – both teaching and non-teaching staff – in no way makes this practice available to all and also does not ensure a high-quality practice. The MOE in Kuwait allocated a total of 800,000 GBP annually for PD activities for all MOE staff where Singapore offers 189 million GBP for teacher PD practice alone. This demonstrates a need to increase support, and teacher PD programmes need time as well as money to make this practice available. Therefore, supporting this practice is a fundamental principle in designing teacher PD practice. Finally, teachers need to be motivated to undertake these activities. One of the ways to achieve this is to link this practice with their career growth, as in Singapore. The idea here is that teachers need to feel that undertaking these activities is a priority and an essential part of their career. Ultimately, these principles were identified by undertaking this research. We do not claim that these are the only principles in designing and providing teacher PD, but these were the result of examining teacher PD practice in Singapore. We believe that Kuwait needs to be aware of these principles when designing and providing teacher PD programmes, and this may help the country to develop this practice and provide outstanding offerings for its teachers. References Alasfour, A. (2017). لمحات تحليلية مقارنة لواقع برامج اعداد المعلم في دولة الكويت. Teacher preparation programs in Kuwait: A profile comparative analysis. World Voices Nexus, 1(1). https://www.worldcces.org/article-3-by-alasfour. (September 2018). Alhouti, I. & Male, T. (2017). Kuwait Principals: Preparation, Induction and Continuing Development. International Studies in Educational Administration, 45(1), 89–105. Bautista, A., Wong, J., & Gopinathan, S. (2015). Teacher professional development in Singapore: Depicting the landscape. Psychology, Society and Education. 7(3): 311–26. Bubb, S. and Earley, P. (2007). Leading and Managing Continuing Professional Development. 2nd ed. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. Bubb, S. and Earley, P. (2010). Helping Staff Development in Schools. London: Sage. Darling-Hammond, L.; Chung, R.; Andree, A.; Richardson, N. and Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional Learning in the Learning Profession: A Status Report on Teacher Development in the United States and Abroad. United State: National Staff Development Council. Earley, P. and Porritt V. (eds.) (2009). Effective Practices in Continuing Professional Development Lessons from Schools. London: Institute of Education, University of London. Jensen, B.; Sonnemann, J.; Roberts-Hull, K.; Hunter, A. (2016). Beyond PD: Teacher Professional Learning in High-Performing Systems. The National Center on Education and the Economy. Available at: http://www.ncee.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/BeyondPDWebv2.pdf. (July 2016). Landman, T. (2008). Issues and methods in comparative politics: an introduction. 3rd ed. London: Routledge. MOE (2006). MOE Unveils $250M Plan to Boost the Teaching Profession. Singapore: Ministry of Education (MOE). Available at: https://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/2006/pr20060904_print.htm (August 2016). MOE (2014). تقرير الاستعراض الوطني للتعليم للجميع بحلول عام ٢٠١٥. [The Report of the National Review of Education for All by 2015]. Kuwait: Ministry of Education (MOE). In Arabic. Morgan, H. (2016). What World-Class Nations in Education Do that Makes them so Good. In: H. Morgan and C. Barry. The World Leaders in Education: Lessons from the Successes and Drawbacks of their Methods. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. Murray, J. (2014). Designing and Implementing Effective Professional Learning. California: Corwin. NIE (2009). A Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century. Singapore: National Institution of Education. Available at: https://www.nie.edu.sg/docs/default-source/nie-files/te21_executive-summary_101109.pdf?sfvrsn=2 (August 2016) NIE (2013). A Diagnostic Study of Education in Kuwait. Kuwait: The National Centre for Education Development. Available at: http://www.nced.edu.kw/images/downloads/NIEreporten.pdf. (December 2014). OECD (2011). Lessons from PISA for the United States, Strong Performers and Successful Reformers in Education. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264096660-en OECD (2014). TALIS 2013 Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264196261-en. Speck, M. and Knipe, C. (2005). Why Can’t We Get It Right? Designing High-Quality Professional Development for Standards-Based Schools. 2nd Ed. California: Corwin Press. Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: an international review of the literature. UNESCO: International Institute for Educational Planning. Yoon, K. S., Duncan, T., Lee, S. W.-Y., Scarloss, B., & Shapley, K. (2007). Reviewing the evidence on how teacher professional development affects student achievement. Issues & Answers Report, REL 2007–No. 033. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest. Available at: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/southwest/pdf/rel_2007033.pdf. (January 2016).

1 Comment

|

AuthorIbrahim Alhouti ArchivesCategories |

- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

RSS Feed

RSS Feed