|

- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

|

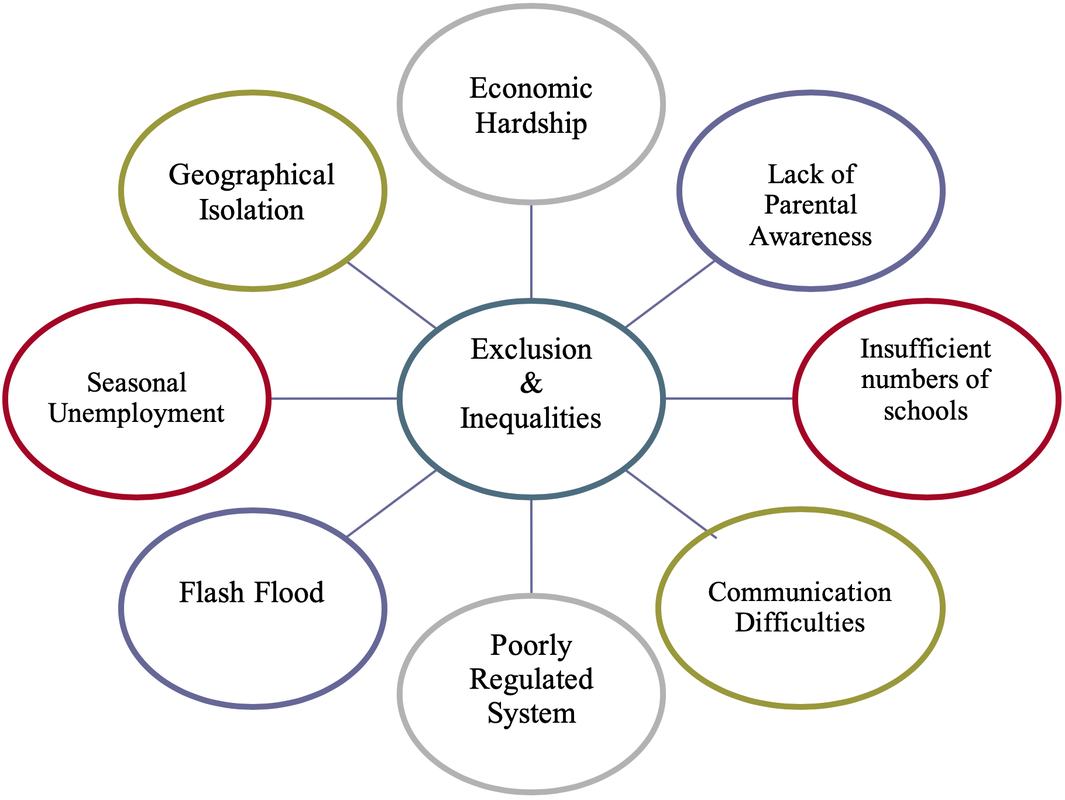

Abstract This study was carried out to investigate the factors that lead to inequalities in access to primary education of the children with certain backgrounds and experiences. The study found that the haor (wetland) areas suffered from few interconnected vulnerabilities such as geographical isolation, flash flood, communication difficulties, seasonal unemployment, economic hardship, lack of parental awareness, insufficient number of schools, poorly regulated system. These factors increasingly marginalized the haor dwellers, and primarily kept the children away from schooling. Based on the findings, the study made some guidelines for policy makers to formulate the pragmatic policy for reducing social exclusion and inequalities in access to primary education of haor areas. Keywords: inequalities, social exclusion, haor, primary education, Bangladesh. 1. Introduction Education is considered as one of the important factors of socio-economic development. It improves the living standard and leads to broad social benefits to individuals and society (Islam, 2014; Manzoor, 2013). Education forms the ground for human capacity development to fit into the society and creates internal solidarity, cohesion and integration among the people (Edward, 2013). Bangladesh has given priority on universal primary education since her independence (Hossain & Mohammad, 2015). In 1990, government passed compulsory primary education legislation (Prather, 1993) and introduced it throughout the country from 1st January 1993 (Zaman, 2014). The National Education Policy 2010 has centered on Education For All (EFA) and Millennium Development Goal (MDG) targets (Chowdhury, 2005). Though primary education is free and compulsory for all, but the children of some geographically isolated areas are lagging behind from this process. They do not avail the opportunity provided for ensuring universal primary education. The haor is a large bowl-shaped floodplain depression with unique hydro-ecological characteristics (Kazal et al., 2010; Mondal et al., 2009). Most of the haors are located in country’s north-eastern part covering about 19,998 sq km of areas (Islam & Hasin, 2014), with 19.37 million people (BHWDB, 2012). During monsoon, haor become extensive water body due to heavy rainfall and overflow of the rivers (Chowdhury et al., 2013). However, in the dry season, this water is drained by the canals/rivers that prepared haor for the farming/crop-production (Alam & Hasan, 2010). The haor areas have special socio-economic and ecological significance (Sharmin & Khan, 2012). It provides a large scale of economic benefits including fish and rice production (Rana et al., 2010). Despite such huge resources, the haor region is lagged behind the overall development of the country (BHWDB, 2012; Gillingham, 2016). Particularly, the inequalities in access to primary education are increasing day by day in this areas. The objective of this study is to investigate the inequalities in access to primary education of haor areas in the context of mainstream Bangladeshi society. 2. Data and Methods Data was collected from both primary and secondary sources. Primary data was collected through Key Informant Interview (KII) and my personal observations. Two KIIs were conducted over phone with one social worker and one government officer. I, myself, was living in haor areas with my family during my boyhood. I was struggling for survival and gathered diverse experiences from haor areas. My personal observations were used as primary data in this study. Secondary data was collected from different books, journals, working papers, newspapers, and reports etc. Both qualitative and quantitative data were used in this study. The collected data were analyzed carefully and presented in textual, and graphical forms to understand the inequalities in access to primary education of haor areas. 3. Results and Discussion The haor areas have special socio-economic and ecological significance (Sharmin & Khan, 2012). Despite such huge resources, haor basin is identified as highly food insecure locality and ‘hot-spots’ of poverty in Bangladesh (Farid, 2017). The inhabitants of this area are mostly poor farmers and fishermen and survive below the poverty line (Alam & Hasan, 2010). Among the haor dwellers, 29.56 per cent live below the lower poverty line (Sumon & Islam, 2013). More than 53 per cent are depending on agriculture for their livelihoods whereas only 12.52 per cent and 2.59 per cent rely on business and fishery respectably (Farid, 2017). The peculiar characteristics of high seasonality of the haor-based economy forces local people to remain out of work for about half of the year resulting in income-poverty (Kazal et al., 2010). Geographical isolation increasingly marginalized the haor dwellers. Because of its distinctive hydro-ecological nature, the haor area gets submerged in water from May to October in every year (Farid, 2017). During this period, the haor dwellers faced severe problems in communication, livelihoods and unemployment. The other major identified problems are: flash flood, lack of proper sanitation, scarcity of drinking water, illiteracy, inadequate health facilities, inadequate infrastructure etc. (BHWDB, 2012). Because of poor living conditions and limited livelihood opportunities, haor dwellers are considered as ‘backward section of citizens’. Frequent natural disasters particularly the devastating flash-floods limit agricultural production. In 2017’s flash-flood affected around 4,667,000 people causing severe damage to the crops, amounting to a loss of about Tk 30400.83 million. This vulnerability leads to food insecurity and significantly curtails their capacity to fulfill the basic needs. Moreover, lack of proper communication and transportation systems are hindering local economic growth, off-farm employment opportunities, and access to health and education. Due to these problems, the haor dwellers are isolating day by day. Latif et al. (2015), however, argued that ‘‘education plays a central role and has a cross cutting impact on all aspects of human life. It is a vital investment for human and economic development.’’ Therefore, education for all and assurance of quality education are the prime objectives of the government (Rahman, 2010). Bangladesh made primary education compulsory for all children between the ages of 6 and 10 (Islam & Mia, 2007). It has achieved significant success in providing universal access to free and compulsory primary education. The net enrollment rate was 97.7 per cent in 2013. The dropout rate has been reduced from 47.2 per cent in 2005 to 20.9 per cent in 2013 (Chowdhury & Rahman, 2015). On the other hand, net enrollment rate among haor area’s children of age 6–15 years was 75.2 per cent in 2009. This rate, at that time, was 82.4 per cent at the national level. The difference between the two figures is 7.2 percentage points (Mehrin et al., 2014). The literacy rate of the haor areas is on an average 38 per cent which is lag far behind the national average. The economic hardship arising from the geographical isolation primarily keep the children away from schooling in haor areas. The haor areas are witnessing highest dropout rate (44 per cent) at primary education compared to that of in other parts of the country (BHWDB, 2012). Poverty, lack of parent’s awareness, migration in town for livelihoods, difficulties in communication and insufficient school infrastructure cause the increasing dropout rate in the haor areas. Parents often withdraw their children from school as a strategy for coping with natural disasters or economic difficulties (GPF, 2013). During the harvest season, the attendance in school is lower. In that time, students engage harvesting with their parents which keep them away from school. The numbers of primary school in haor areas are lower than any other parts of the country. In many villages there are no primary schools. The communication difficulties hamper normal schooling in haor areas. During the rainy season, the haor turns worse because of strong waves. Then the boat journey is become very dangerous for fatal accidents. Parents are naturally reluctant to send their children to primary schools in distant locations. Even the children those are enrolled in distant schools, flooding makes their attendance irregular. During dry season students have to walk miles to get to school. Moreover, teachers are unwilling to stay in haor areas due to the difficulties they experience at the local level. Figure-1: Causes of social exclusion and inequalities in primary education of haor areas Source: Prepared by author’s personal observations, 2017 Sparkes (1999) argued that low levels of educational attainment are crucial in generating and sustaining social exclusion. Ferdaush (2011) showed that inequality is a part of the social structure. Socio-cultural norms, religious matter, lack of parental education and less expectation for girls’ education create inequality in primary education. The present study found that ‘social exclusion’ and ‘inequalities in primary education’ are mostly correlated. Social exclusion has appeared as a major barrier in achieving universal primary education in haor areas. Figure-1 reveals that social exclusion and inequalities in primary education of haor areas are increasing due to various reasons including lack of parental awareness, economic hardship, flash flood, insufficient numbers of schools, and communication difficulties.

Education plays a vital role in development process. It is closely associated with rapid economic growth (Alam, 2008). Any country can reach the peak of development if they can educate the people of their country (Hossain et al., 2014). None of the industrialized countries achieved significant economic growth before attaining universal primary education (Rong & Shi, 2001). Akhter (2015) showed that education increases an individual understanding, improves living standard, enhances productivity, and improve work skills. Parziale & Scotti (2016) argued the aim of the education system is to expand the socialization of citizens. Education is a crucial factor in ending poverty, broadening employment opportunities, increasing income levels and improving maternal and child health. 4. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations The present study found that the geographical isolation and socio-economic vulnerabilities of haor inhabitants limit access to the primary education. The findings show that inequalities in access to primary education are the major problems in haor areas. Therefore, this area deserves special development initiatives from the government site as it covers a major part of the country and population. Without developing haor region, the country’s overall progress will not be achieved at all. The pragmatic steps should be taken for creating the justice in access to primary education in haor areas. The following recommendations should be considered in this regarded: l For reducing the intensity of flash-flood, regular dredging of the rivers, and canals should be ensured. Sufficient web protection wall should be built to reduce losses of lives and properties of haor dwellers. l Without proper communication and transportation facilities, the sustainable development of haor areas will not be achieved. In this purpose, more submersible roads and roads approaching schools should be build in this areas. l The primary schools for haor areas should be designed to serve multiple purposes so that they can use the school building at the time of natural disaster. Schools should be equipped with qualified teachers, tube wells, latrines and meals during school hours. l A special academic calendar should be introduced and the summer vacation schedule should be readjusted for haor areas so that students can help their parents during the harvest time without compromising their school hours. l A separate payment structure should be introduced for the teachers in haor schools. Each school should be provided with some boats as means of transportation for the students during the monsoon period. l For attaining the various development schemes for haor dwellers, the sufficient logistical supports and financial autonomy of Local Government Institutions (LGIs) should be ensured. In addition, an effective coordination between LGIs and NGOs should be established l A strong political commitment and special allocation of funds from the government are needed for the development of haor areas. It is highly needed to set up a separate ministry for fulfilling this purpose. l Access to adult and lifelong education, as Bradshaw et al. (2004) said, can play a significant role to reduce social exclusion in haor areas. l For creating more sustainable livelihood, the government should undertake some skill development programmes and alternative employment opportunities for the haor dwellers. Some non-agriculture based employments should be created especially during the off-firm season. l Educational policy should be modified particularly emphasizing on improvement of haor education. Parziale & Scotti (2016) argued that educational policies have positive effects on the economic system if they are oriented to reduce socio-economic inequalities increasing the rate of social inclusion. l Haor people should also realize their own rights and should learn the ways to press demand from the government bodies to ensure their rights. 5. Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge Professor David Turner, Institute of International and Comparative Education, Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, China for his invaluable comments on an earlier draft of this article. I am also thankful to the WVN’s editor and anonymous reviewers for their in-depth and constructive feedback throughout the process. However, I am only responsible for the material and opinions expressed in this paper. 6. References Akhter, M. (2015). The Role of Education in Human Resource Development in Bangladesh. Banglavision, 15(1), 39-54. Alam, M. K., & Hasan, M. R. (2010). Protection Works Against Wave Attacks in the Haor Areas of Bangladesh: Analysis of Sustainability. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries, 15(2), 69–85. Alam, G. M. (2008). The role of technical and vocational education in the national development of Bangladesh. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 9(1), 25-44. BHWDB (2012). Master Plan of Haor Area. Dhaka: Bangladesh Haor and Wetland Development Board (BHWDB). Bradshaw, J., Kemp, P., Baldwin, S., & Rowe, A. (2004). The drivers of social exclusion: A review of the literature for the Social Exclusion Unit in the Breaking the Cycle series. London: SEU/ODPM. Chowdhury, I. A., Zakaria, A. F. M., Islam, M. N., & Akter, S. (2013). Social capital and resource conservation in “Community Based Haor Resource Management (CBHRM) Project”: A Case from Bangladesh. Spanish Journal of Rural Development, IV (3), 21-34. Chowdhury, W. S. (2005). How Universal is Universal Primary Education in Bangladesh: A Case Study of the Haor Area (Unpublished Master Dissertation). Institute of Social Studies (ISS), The Hague. Edward, L. N. (2013). Politicisation of Education in Nigeria: Implications for National Transformation. Global Journal of Human Social Science (F), 13(5), 22-33. Farid, S. (2017, November 10). In search of a development model for haor dwellers. The Daily Observer. Ferdaush, J. (2011). Inequality in Primary Education of Bangladesh. Dhaka: Unnayan Onneshan. Gillingham, S. (2016). CARE Bangladesh Programme Strategy: Haor Region 2015–2020. Dhaka: CARE Bangladesh. GPF (2013). Accelerating Progress to 2015: Bangladesh. Good Planet foundation (GPF). Hossain, J., Hoque, M. A., & Uddin, M. J. (2014). Private University: In Expanding Higher Educational Facilities in Bangladesh. Banglavision Research Journal, 14(1), 49-56. Hossain, M. M., & Mohammad, A. M. (2015). Higher Education Reform in Bangladesh: An Analysis. Workplace, 25, 64-68. Islam, M. T., & Hasin, F.S. (2014). Malnutrition among 3-5 Years old Children in the Haor basin of Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature, 2(7), 167-172. Islam, M. R. (2014). Education and Economic Growth in Bangladesh-An Econometric Study. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 19(2), 102-110. Islam, M. R., & Mia, A. (2007). The role of education for rural population transformation in Bangladesh. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 8(1), 1-21. Kazal, M. M. H., Villinueve, C., Hossain, M. Z., & Das, T. K. (2010). Food Security Strategies of the people living in haor areas: status and prospects. Dhaka: NFPCSP. Latif, A., Choudhary, A. I., & Hammayun, A. A. (2015). Economic Effects of Student Dropouts: A Comparative Study. Journal of Global Economics, 3(2), 1-4. Mehrin, M., Yasmin, N., & Nath, S. R. (2014). Geographical Exclusion to Educational Innovation: A Study on BRAC Shikkhatari. Dhaka: BRAC. Mondal, M. S., Kouchi, Y., & Okubo, K. (2009). Sedimentation and Thermal Stratification During Floods: A Case Study on Hail Haor of North-East Bangladesh. Journal of Hydrology and Meteorology, 6(1), 15-25. Manzoor, H. (2013). Measuring Student Satisfaction in Public and Private Universities in Pakistan. Global Journal of Management and Business Research Interdisciplinary, 13(3), 4-15. Prather, C. J. (1993). Primary Education for All: Learning from the BRAC Experience: A Case Study. Washington, DC: Academy for Educational Development. Parziale, F., & Scotti, I. (2016). Education as a Resource of Social Innovation. SAGE Open, 6(3), 1–9. Rahman, M. A. (2010). Commercialisation of education in Bangladesh: Problems and solutions. NAEM Journal, 5 (10), 1-11. Rana, M. P., Sohel, M. S. I, Akhter, S., & Alam, M. S. (2010). Haor based livelihood dependency of a Rural Community: A Study on Hakaluki Haor in Bangladesh. Proceedings of the Pakistan Academy of Sciences, 47(1), 1-10. Rong, X. L., & Shi, T. (2001). Inequality in Chinese Education. Journal of Contemporary China, 10(26), 107–124. Sharmin, S. & Khan, N. A. (2012). Gender and Development amongst a Wetland Community in Bangladesh: Views from the Field. OIDA International Journal of Sustainable Development, 3(4), 11-21. Suman, A., & Islam, A. (2013). Agriculture Adaptation in Haor Basin. In R. Shaw et al. (eds.), Climate Change Adaptation Actions in Bangladesh (pp. 187-206). Japan: Springer. Sparkes, J. (1999). Schools, Education and Social Exclusion. London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion. Zaman, M. M. (2014). Dropout at Primary and Secondary Level: A Challenge to Ensure Rights to Education for the Government of Bangladesh (Unpublished Dissertation). BRAC University, Dhaka.

1 Comment

|

AuthorMd. Bayezid Alam ArchivesCategories |

- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

RSS Feed

RSS Feed