- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

|

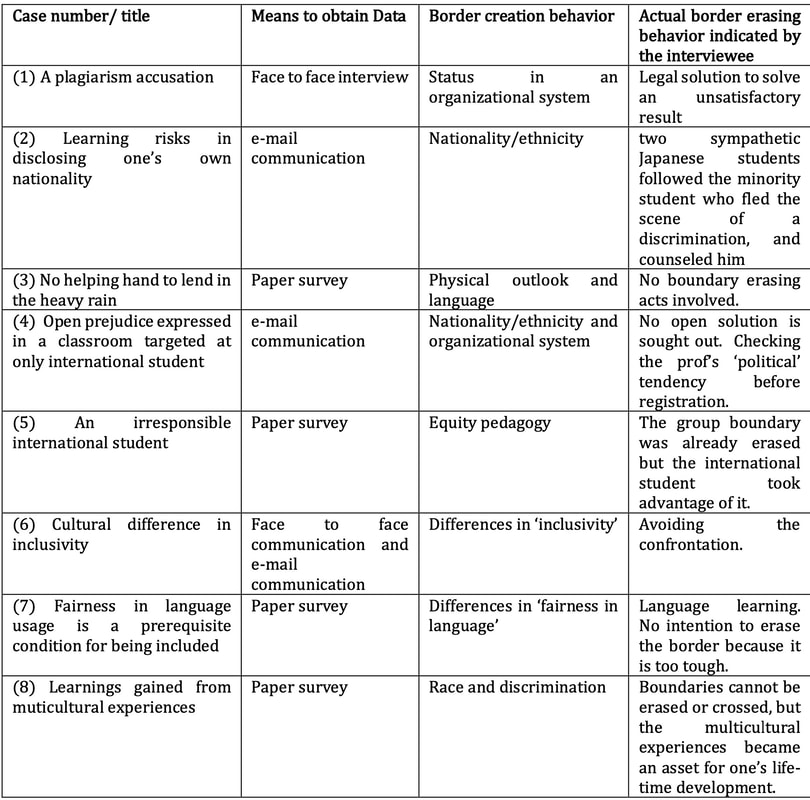

Introduction Our modern world is becoming globalized and the way of “human togetherness (Bauman, 2012, vii)” is changing in a various part of our lives. Bauman (2000) introduces the concept of solidity versus liquidity of modernity in which “the old ways of doing things no longer work, the old learned or inherited modes of life are no longer suitable for the current conditio humana, but when the new ways of tackling the challenges and new modes of life better suited to the new conditions have not as yet been invented, put in place and set in operation . . . (Bauman, 2012, vii)” “A model of global society (Bauman, Ibid.)” has not been known yet, “Instead, we react to the latest trouble, experimenting, groping in the dark(Ibid.).” The features of liquidity hold “fragility, temporariness, vulnerability and inclination to constant change, (Ibid.viii)” The liquidity of modernity is “A(a)n effect of that quest for solidity(Ibid, ix)” which signifies “perfection,” “order-obsessed and compulsively order-building modern powers (Ibid.)” and “ultimate solutions (Ibid.)”, “ideal condition to be pursued of things and affairs (Ibid.)” According to Bauman(Ibid.), “the cause of the solids melting was not resentment against solidity as such, but dissatisfaction with the degree of solidity of the extant and inherited solids: purely and simply, the bequeathed solids were found not to be solid enough (insufficiently resistant or immunized to change) by the standards of the order-obsessed and compulsively order-building modern powers (Ibid., ix)” The multiculturalism in a global modernity of Japan is the focus of the question; Is current multiculturalism in Japan a desirable form for international students? The current research will inquire what aspects, issues, communication forms would be resisting against changes that are needed to be melt down to become liquid multiculturalism in Japan. The current study chooses Japan in which strong solidity is found in various phases of life as known as formality (Omote, in Japanese) (Doi, 1985) that requires very different expectation to manifest in a manner of communication in daily lives, as opposed to informality (Ura, in Japanese)(Doi, Ibid.). Therefore, the solidity of multiculturalism in Japan is likely to be found quite rigid. In other words, the Japanese carry the concept of solid multiculturalism as treating “the other” or “foreigner” in different group formation from native Japanese. In the interaction of Japanese themselves, both in formal and informal aspects of Japanese social interaction require numerous groupings that are formed regardless of conscious effort, and that plays as a positive energy to sustain solidity of traditional social interactions in Japan. Among similar groupings, competition is always assumed in life. On the contrary, the concepts of uBuntu in Africa present an extremely liquid way of relating to others as not been perceived as “competitors” (Kamlesh, 2013). uBuntu is explained as a philosophy, as articulated by Kamlesh (2013): “An anthropologist proposed a game to children of an African Tribe. He put a basket of fruit near a tree and told the kids that the first one to reach the fruit would win them all. When he told them to run they all took each others’ hands and ran together, then sat together enjoying the fruits. When asked why they ran like that, as one could have taken all the fruit for oneself, they said, “UBUNTU, how can one of us be happy if all the others are sad?” ‘UBUNTU’ is a philosophy of African tribes that can be summed up as “I am because we are.” In Japan, children learn from early age whose hands can be taken, or who is in your group. However, this grouping boundary is fluid so that children have to follow all the cues known to them. This even includes learning situations, in which a child tries to get help from other students in a formal education situation may be punished and called a “cheater.” The fluidity of grouping boundary is not the nature of human interactions in Japan, because once you are determined your career at the age of 18, when one graduates from a high school, 22 when one graduates from a college, this person’s entire career ladder is almost determined then. The difference between Japanese solidity and the expectation from international students who assume uBuntu, for example, is not expected when they come to Japan, in which cultural, gender, language, race, ethnicity, age, nationality, company, school from which one graduated, and a host of other qualitative conditions exist that serve as a source of forming various groups. In Japan, there is a concept called Omoiyari (empathy), which plays to calm down the conflicts stemmed from the different cultural or any other differences. It seems to hold the similar philanthropic humanity as uBuntu, but the range of groupings that utilize this concept seems extremely small, and the boundary seems unclear to international students in Japan. Therefore, the difficulties experienced by international students appear many times, and in many places. From the Japanese perspective, it is the boundary creation activities. The boundaries are to discern the different groupings, such as status as in a hierarchy, nationality, race, ethnicity, and so on. The current study of international students’ experiences in Japan as a form of insight of dissatisfaction with the “solidity of the extant and inherited solids (Bauman, ix)” of Japanese way of elaborating multiculturalism of the modernization. The uBuntu supplies the direction or a hint toward liquefying of multiculturalism that are perceived as a part of modernity in Japan in a form of less structured, and less group oriented “human togetherness (Bauman, 2012, vii)”. The question that benefits universal situation is, how can host people and guest international students’ respect and dignity be secured after knowing the context and the issues of dissatisfying solidity of multiculturism that is not from ideal. The application can be anywhere in the world because ‘uprooted’ people are moving from one site to everywhere, and the essence of liquidation of solid multiculturism can be a treasure to anywhere. This current study presents multicultural episodes that were obtained from various international students who attended university in Japan. There are eight cases that show the difficulties they had in various areas. The analysis is about the boundary creation of groupings within which Japanese sense of empathy which is usually centered around humanity and seems to be practiced in the range of groupings. The humanity that is practiced in Japan is based on the “same group of people” so that one holds the sense of “human togetherness (Ibid.)”. In this study, the difficulties are understood as the different expectations for the boundaries that are defined to separate different groupings. Through the difficulties expressed in the situation of multicultural interactions, boundary creation effort becomes clear, and therefore, uBuntu or empathetic effort will not be applied, if one is situated outside the boundary. Therefore, those who do not belong to the innate groupings, are considered “outsiders” and will not be a recipient of empathetic interactions. This study is to find the emic (subjective) categories of Japanese group concepts by examining the conflicts that occur when international people interact with Japanese people. The final suggestion is to expand the boundary on the side of Japanese and the Japanese university system, and at the same time, to let the international students inputs/ideas into the Japanese system to receive the uBuntu spirit. The methods of voicing should be effective, so that their voice is heard, loud and clear. This is for melting down the solid multicultural state in Japan. In this study, the overarching question is, “what do international students’ multicultural difficulties imply for Japanese and international students themselves?” In other words, how can the solid state of multiculturalism in Japan be melting down at individual context where people’s stereotype is rigid, resources available to international student is limited, and further, the power struggle means is not known at all by the international students. Barth (1969) suggests three stages of co-existing in a geographical area. “(1) They may occupy clearly distinct niches in the natural environment and be in minimal competition for resources. . . (2) They may monopolize separate territories, in which case they are in competition for resources and their articulation will involve politics along the border, and possibly other sectors. And (3) they may provide important goods and services for each other, i.e. occupy reciprocal and therefore different niches but in close interdependence (Ibid., p. 19).” International students in Japan have to start out creating niches for themselves, with limited hegemonic resistance across difference. Within a multiplicity of boundaries, they have to find the means to melt the solidity and convert to liquidity to survive. Are they creating community of difference, as Barth (1969) indicates, or do they attempt to organize themselves to make recognizable voice to maneuver the way as immigrant? If the multicultural context is stubbornly solid such as the case in Japan, how can they promote the liquidation of the multicultural state in Japan? Methodology Surveys were distributed to approximately 500 international and Japanese students at a national university in Japan in 2018, and supplemented by face-to-face interviews with them. First, an e-mail message soliciting the participation to the research was sent to about 100 international students on campus through a listserve. As a result, no single reply was made. Then, a paper survey was distributed to the five international dormitories which holds approximately 100 residents per dormitory. While putting one sample on the bulletin board in a dormitory, a small box with sample question is placed to cast the paper reply. Collection of reply was made twice a week at five locations for about one month, tallied and numbered. As a result, 42 workable replies were made. In order to cover the place that is related to international activities on campus, a box is placed at an international center which has some international programs are taken place, but no reply was yielded from it. In addition, individual contacts were made with international students who previously replied and wrote the stories of uncomfortable experiences in their lives. After hearing a sketchy story, e-mail communication was taken place to clarify or for more details. Questions are around various difficulties, such as: unhappy/harsh/sorry/sad/life threatening/ego threatening/upsetting/devastating experiences in Japan. The episodes that showed multicultural difficulties were looked for, and the opinions and solution were asked.[1] The survey was created in Japanese and English languages. Data obtained There are 42 workable cases yielded from the survey. The summary is attached (appendix 3). Among them, two persons took face-to-face interview, one person took face-to-face and e-mail interview to supplement the answer. Five persons answered with e-mail message exchange, and among them, one person had also paper response. The rest 34 individuals responded in a paper. Composition of respondents is as follows. Gender shows eleven females and thirty-one males. Academic status shows eighteen undergraduate level students, seven graduate level students, and the rest includes three research students, one clerical person, four researchers and one visiting faculty. The countries include eleven people from China, six from Germany (among them, one from both Germany and Japan), four from Korea, four from Malaysia, two from Indonesia, two from Japan (among them, one stayed in China for ten years), and one from Bangladesh, Egypt, France, Iceland, India, Kenya, Romania, Sweden, Taiwan, Tanzania, Thailand, United States of America, and Zimbabwe. Length of stay in Japan varies from two days to eight years except a Japanese who has never been abroad. The proficiency of Japanese language among international students also varies from “none” to near native level. The data are organized and clustered in eight cases in terms of border creation behavior that suggests to deliniate the solid group formation in Japan. The actual border erasing behavior indicated by the interviewees was also listed. This border erasing behavior is assumed to suggest “melting” of solid multicultural state of Japan. [1] This study is the secondary analysis of the original text data which displays the analysis on identity and empowerment, “Experiences of international immigrant students in a Japanese University: An in-depth study” in Gross, Z., ed. (2020). Migrants and Comparative Education, Call to Re/Engagement.Brill., 268-279. Appendix 1 attached below contains the details of the eight cases showing dissatisfaction on the current multicultural state in Japan, which are summarized in Table 1. Table 1: Eight cases showing dissatisfaction on the current multicultural state in Japan In the chart, “Border erasing behavior” shows various concrete levels of behaviors, from technical solution to basic education due to the nature of problems and the wording of the interviewees. Discussion and Conclusion This study looked into the “solidity of modernity (Bauman, 2012) ” in the area of multiculturalism from the dissatisfaction with it in Japan expressed by international students who attend at a Japanese university. Interviews and surveys of international students on uncomfortable experiences revealed the group boundary creation practices in Japan that contribute to the solidity afirmation of multiculturalism in Japan. It is not liquidity of modernization practices such as seen in uBuntu philosophy in Africa, international students presented various issues to confront with the respect for their dignity of their identities. The identity is to be recognized and being included in a group in various scenes, and the dignity is being acknowledged and respected as a full-fledged identity, not ignored, nor being through. In order to be included in a group, cultural differences must be taken into consideration, but they are not always being well awared. For example, the case (1), the posesser of the knowledge is assumed to be different from culture to culture. Therefore, the citation that is needed to be acknowledged in a term paper may not be same in a different culture such as Japan. Yet, an international student has to learn the different rule of citation, and if he/she won’t follow the new rule, the punitive measure is strict. The instructors in the host culture have to teach such a rule in advance, not to punish after the incident, to save the face of the international student. Along the same line, the manner to point out the rule breaking behavior should be with sensitivity, not violently taming international student. The lesson for the liquidity is the substantial change in orientation for the international students and sensitive training of the instructors. Care for international students’ respect and dignity does not need the authorities to lead the groupings, such as circle activities. However, this case (2) Learning risks in disclosing one’s own nationality, lacks the additional educational opportunity for Tanaka, the Japanese who started the remarks to an international student. Someone has to follow to prevent the offender from repeating the same behavior. The case (3) No helping hand to lend in the heavy rain, needs extensive educational reforms toward liquidity multiculturalism in Japan. The willingness to help was absent may suggest these Japanese may not be willing to associate a foreign looking person. The issue is the knowledge of universal assumption regarding human beings. If the multiculturalism is a solid separation of international students from Japanese students, Japanese would never try to associate with international students forever. Therefore, liquidation is desirable in various ways. The case (4) Open prejudice expressed in a classroom targeted at only international student, requires the sensitive training on the instructors side. Ethnocentricism and stereotypes must not be allowed in the classroom. At the organizational level, a help line or some sort to rescue victims is needed. At the university level, the policy should reflect its standing without discriminatory practices, and solicit to accept the claims without much tedious procedures. Judicial board should be furnished, and both sides have to be allowed to practice basic human rights. The bottom line is to protect international students from unreasonable accusation that creates fear on the part of international students. The case (5) an irresponsible international student, shows the fact that international students should be aware of basic social manners. This indicates, both host and guest parties have to know how the interactions should be taken place at an educational scene. In the orientation, and the first day of the class, students have to be taught to greet each other, introduce themselves to each other to open up the communication. If the multiculturalism holds solidity, in which both parties are placed geographically at different places, both parties never develop such common courtecy. The dormitories used in this study are designed for international students only, so their complaints about lack of interaction with host student body is extensive. We cannot start to respect international students without meeting with them, first, and vice versa. (6) Cultural difference in inclusivity, shows the insensitive remarks about the international student’s identity thrown by a peer worker, and he is not accepting the following justification remarks of exclusion from his fellow countrymen. One’s identity issue is fairly complex, but people are careless about making stereotypes. Furthermore, in this case, the justification followed, but that shallow justification made him angrier. Sensitivity training is necessary especially among those who deal with customers. Refrain from making judgement on one’s identity is required to show the respect for dignity of international student. In this case, the highest fluidity of multiculturalism is necessary to refrain from cultural stereotypes. (7) Fairness in language usage is a prerequisite condition for being included, has the practical point, to handle the ambiguity, a certain level of language capability is expected. To own the respect, to save the dignity, an advance level of language capability is expected as anyone who goes into different cultures know. To earn the understanding from the local host people, the best way might be to let them learn one or two foreign languages. However, it is not practical to wait until an international student be able to academically function in a foreign language such as Japanese. It might take at least 15 years to be able to read the local newspapers that is usually used as an indicator of learning language difficulty. Let’s be practical to satisfy both parties in a short period of time, by using English, the de-facto universal language, for the basic functional level. Japanese system holds solidity in the past in this regard, but quite recently, due to the global economic interactions, the entire society started showing the shift toward liquidity in multiculturalism, presenting information in several languages when they are needed. (8) Learnings gained from muticultural experiences provides values and attitudes in multicultural interactions. The simple attitude and value regarding “ otherness » is changing, that is a must to hold respect for dignity of others. If one is treated with stereotypes, international students search for the reasons to understand and accept it. However, unreasonable stereotypes stick in the mind for a long time. If uBuntu philosophy is appreciated, then, empathic attitude will be taken place, so that those who were victims of stereotypes may not place another stereotypes onto “ others ». As the last case expressed the learning from cultural differences, a complete understanding by erasing the borders may not be possible, but the liquidity of multiculturalism is possible to carry on. It is concluded that latent or apparent group formation regarding above issues appears critical for a change in creating “ human togetherness (Bauman, 2012) “ that signifies liquidity of modernization. References Banks, J. A. (1995). Handbook of research on multicultural education, MacMillan Publishing USA. Banks, J. A. (1994). An introduction to multicultural education, Allyn and Bacon. Barth, F. (1969). Ethnic groups and boundaries: The social organization of culture difference. Waveland Press. Bauman, Z. (2012) Liquid Modernity, Polity Press. Doi, T. (1985) Omote to Ura, Kobundo. Hampden-Turner, C. and i TROMPENAARS, F. (2000). Building Cross-Cultural Competence. Yale university Press. Kamlesh, K. K. (2013). ”UBUNTU” – I am because we are (African Short Story) https://soulbulbs.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/ubuntu2.jpg

0 Comments

|

AuthorDr. Hisako Inaba ArchivesCategories |

||||||

- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

RSS Feed

RSS Feed