- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

|

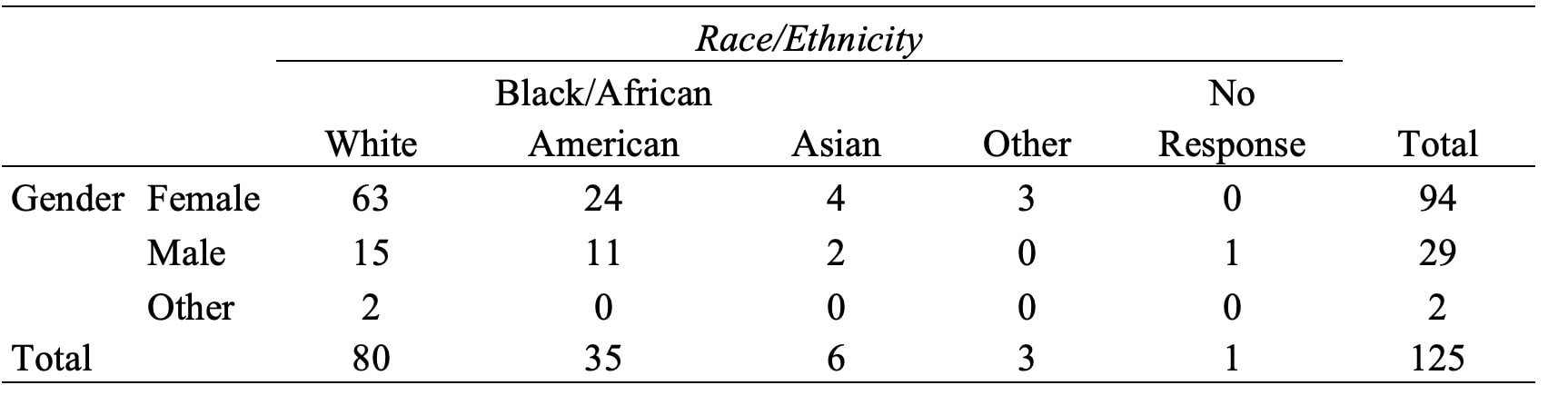

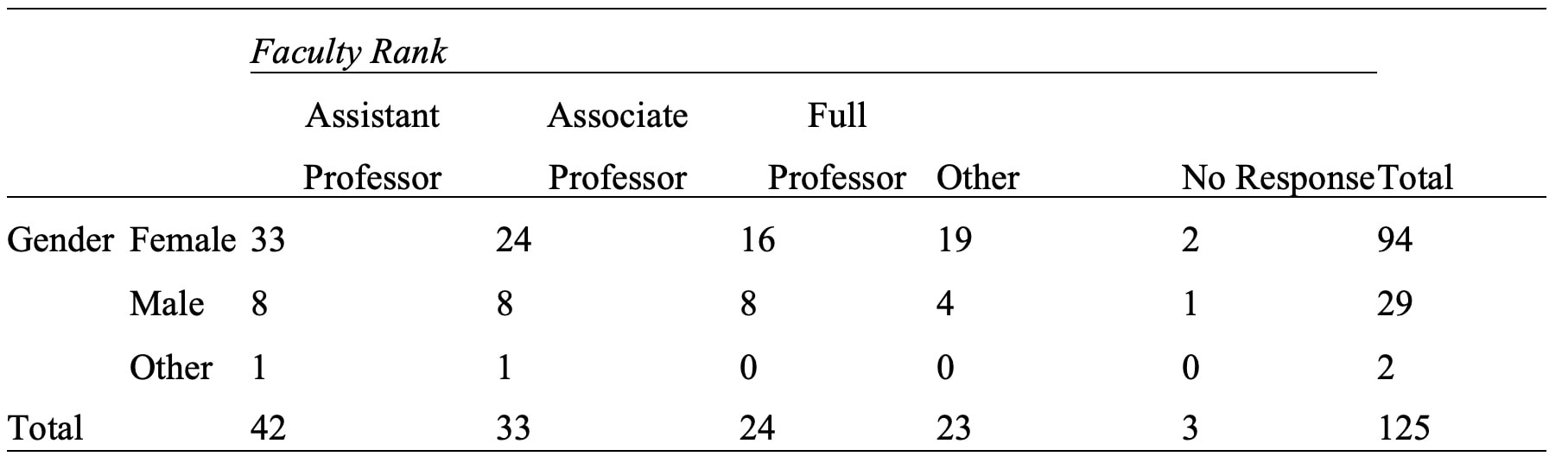

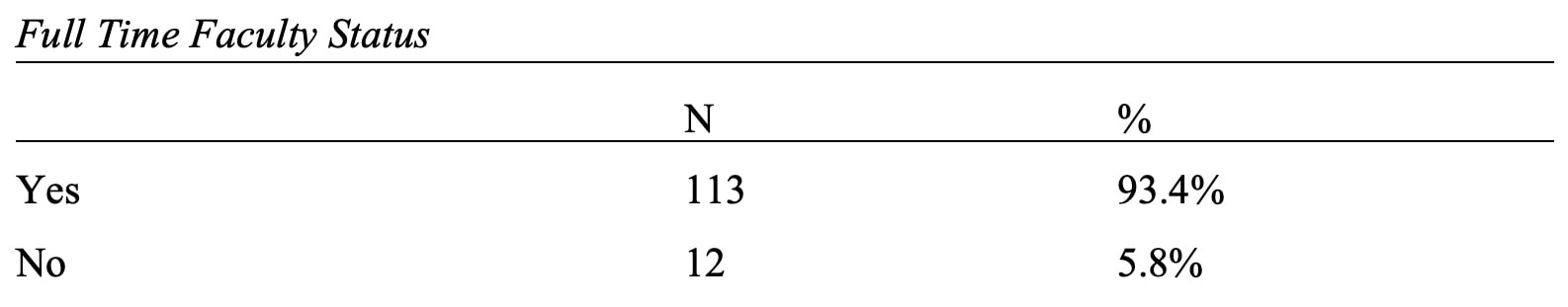

Abstract The research presented in this paper is part of a larger explanatory, mixed-methods collective case study that examined the impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic on the productivity of full-time, tenured and tenure track or probationary faculty. This paper presents a qualitative analyses of the participants’ narrative elicited from three prompts/open-ended questions included in the survey. The participants noted a shift in responsibilities that prioritized teaching to maintain continuity of instruction during the global pandemic. Additionally, community-engaged work was impacted by the health concerns associated with the pandemic. Keywords: Community-engaged scholarship; faculty productivity; perceptual survey; qualitative analysis. Introduction The National Education Association (2020) wrote “The COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented challenges to our schools, our economy, and our nation’s families, exacerbating racial inequities and placing a disproportionate burden on communities of color throughout the country” (p.2). In February 2020, colleges and universities were notified by health care officials of the looming threat of COVID-19 (Fischer, 2020). Despite early efforts to minimize faculty and student travel to regions impacted by the pandemic (Fischer, 2020), “colleges [were not] prepared for the disruptions to our working lives caused by the global pandemic” (Lake, 2021). After March 2020, announcements of short institutional closures, followed by extended campus-wide shutdowns were widespread (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2020). To facilitate the continuity of instruction during the pandemic, faculty members transitioned their courses from face-to-face instruction to courses infused with technological instructional strategies (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2020; Darby, 2020; McMurtrie, 2020a, 2020b). The COVID 19 global pandemic immediately reshaped faculty work life. “Though exceptions exist, three elements (Roles) typify tenure-track faculty work: research, scholarship or creative activity [Research]; teaching, mentoring and advising [Teaching]; and community and professional service [Service]” (Hardré & Cox, 2009, p. 383). Expectations for faculty performance in these three areas are mitigated by what institutions value the most (Jamali et al., 2022); research-intensive institutions often prioritize research productivity in the form of grant procurement and publishing (Boyce & Aguilera, 2021), while teaching institutions may emphasize evaluation of teaching and student evaluations. For faculty at traditional brick and mortar institutions, the pandemic required faculty to transition their Spring 2020 courses to remote instruction while designing Summer 2020 courses that were entirely taught remotely or online. The purpose of this explanatory, mixed-methods collective case study was to understand the impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic on the productivity of full-time, tenured and tenure track or probationary faculty. At this stage in the research, faculty productivity is generally defined as some combination of research, teaching, service, and community-engaged work. This study was guided by the following research questions: 1) How did full-time faculty describe their experiences teaching, conducting research, and facilitating community-engaged work during the COVID-19 global pandemic?; 2) What were faculty perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on productivity in the areas of teaching, research, and community-engaged work?; and, 3) Given the ongoing nature of the global pandemic, what policies and practices could campuses adopt to better support faculty productivity? This paper explores the type of community-engaged work undertaken by participants prior to the pandemic and how that work was reshaped by the pandemic. Review of Literature Tenure and promotion for faculty involves evaluation of their teaching, research, service and/or community-engaged work. Research intensive and the culture of publish or perish aside, success at a Primarily Undergraduate Institutions (PUI) requires “excellence in teaching, mentoring and a significant component that engages undergraduates in meaningful ways leading to scholarly works and documented student success” (Vega & Hengartner, 2021). Concerned about narrow conceptions of faculty research, Boyer (1990) posited an approach to research that encompassed faculty work as teachers, scholars, citizens, and communicators (Crow et al., 2018). This broader conceptualization of faculty work emerged as community-engaged or community-based work. The inclusion of community-engaged work as one criterion in the tenure and promotion process has been challenged by the ability of faculty to demonstrate the impact of their community-engaged work on the communities served. Unlike the impact factor of a manuscript in a journal, the challenge continues to be how to demonstrate the impact of community-engaged work during the tenure and promotion process. Efforts to broaden how research is operationalized in the tenure and promotion process is essential as the number of faculty invested in leveraging their professional expertise to solve societal challenges increases. Research Design This research study employed an explanatory, mixed-methods collective case study that involved two phases of data collection (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Creswell & Creswell (2018) described a unifying issue or event that binds multiple participants in a collective case study. This research design was employed to examine the impact of the global pandemic on faculty’s teaching, research, and community-engaged work. In the first phase of the study, the researchers implemented a perceptual survey using Qualtrics (a web-based survey research platform). The survey examined faculty’s experiences teaching, engaging in research and community-engaged work before and after the onset of the global pandemic. The perceptual survey included thirteen demographic questions, fourteen Likert-scaled questions about the participants professional experiences before and after COVID-19; and three open-ended questions wherein participants reflected on the impact of COVID-19 on their teaching, research, and community-engaged work. The second phase of data collection involved focus groups and individual interviews. The questions guiding these interviews were derived from an analysis of the data generated from the perceptual survey. The focus of this paper is the analysis of the participants’ narratives elicited from the three prompts/open-ended questions included in the survey. Sampling and the Participant PopulationThis study relied on snowball sampling. Vogt & Johnson (2016) described snowball sampling as a process wherein the researchers identify initial participants who, in turn, connect the researcher to additional participants (p. 414). This study focused on full-time, tenured, and probationary or tenure track faculty. We particularly focused on this population within the faculty ranks because of the potential impact of shifts in instruction (teaching) on the generation of new knowledge (research) relevant to real world contexts (community-engaged work). The ongoing nature of the global pandemic made conducting research a challenge. The researchers recruited participants using social media networks, like Facebook and Twitter; and email distribution lists of professional associations to disseminate the invitation to complete the survey. The researchers recruited participants from January 2021 through April 2021. Data Analysis The analysis of the data included in this paper resulted from three, open-ended prompts/questions included on the perceptual survey that we implemented. The following prompts were included on the survey: ● Generally, describe your research and community service activities prior to the onset of the global pandemic. ● How did the global pandemic impact your productivity as a faculty member? Please discuss how the pandemic impacted your teaching, research, and any service or community engaged work. ● Consider your life as a faculty member in Fall, 2020. Discuss how your professional life has been impacted by the global pandemic. Participants’ responses to the aforementioned prompts were extracted from Qualtrics; documents with participants’ responses for each prompt (resulted in three documents) were imported into Atlas.ti for analysis. The narratives were analyzed during two-cycles of coding. During the first cycle of coding, the researchers categorized the narrative using themes that emerged from our reading of the narrative. During the second cycle of coding, the data assigned to each code was used to construct a collective picture of the community-engagement undertaken by participants before the pandemic and how that work was reshaped because of the challenges of the times. There were 139 respondents. After deleting incomplete surveys, 125 participants or 89.9% of the surveys were included in the analysis. The population that completed the survey were not representative of faculty demographics in the United States; typically, faculty in the US are more likely to be white and male. Because we relied on convenience sampling, women were overrepresented among the participants; approximately 40% of participants were white females, aged 41-50, who were full-time tenured professors or are on tenure track. Additionally, they worked at public, predominately white institutions that tended to value research and teaching equally. Table 1: Race and Gender Table 2: Faculty Rank by Gender Table 3: Faculty Status Faculty’s Service or Community-Engaged Work and COVID

For the faculty who completed the survey, life abruptly changed because of COVID. ‘Sharon’ wrote, “It has been hard to do much other than teach and do the additional service I took on”. The type of community-engaged work or service undertaken by faculty prior to the onset of the COVID-19 global pandemic could be grouped into the following categories: scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL); service to the community through volunteerism; and, consultancy work. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning or SoTL Hutchings & Shulman (1999) characterized the SoTL as a process wherein a “faculty member…systematically investigates questions related to student learning” (p. 13). The purpose of such an inquiry is to improve one’s own pedagogical practice and to replicate practices that contribute to the field. For many faculty, engaging students in community-based work is part and parcel of the SoTL. ‘Samantha’ wrote: [C]ommunity engaged work came to a halt at the onset of the pandemic. I was working with students [in a] capstone course where they were collecting data at a local homeless shelter. [Afterwards], worked with shelter to allow some students to conduct telephone interviews with staff as an alternative. ‘Daphne’ said “Internship demands [were] ridiculously greater as interns [were] trying to work with the challenges of remote learning.” ‘Denise’ concurred: It has also been challenging to do outreach work and gather with students to design/develop new projects. Increased concerns about student safety and health, especially when completing school and clinical counseling positions. There has been an increased request for information about where students are placed/completing their practicum/internship. School closures impacted internships and practicuum placements, but for faculty whose research was classroom-based, “[t]he pandemic impacted [their] ability to connect with the community and public schools”. ‘David’ continued to write [The pandemic] had its greatest impact on service to the community. It also had an effect on my research due to lack of access to schools. When we went totally virtual and did not return to campus it was difficult to collaborate with others. For faculty engaged in international work, “all travel was banned” recounted‘Sylvia’. Service and Consultancy The global pandemic immediately impacted faculty teaching, after all “[o]nline content creation is time consuming, which took away time from my scholarship and service” shared ‘Taren’. And the nature of community-engaged scholarship changed because of the challenges associated with collaboration and the need to social distance. However, respondents like ‘Taylor’ talked about the changes to the conditions of their service. [W]hen the pandemic started … students [were] in distress, [we made] accommodations for students. Every morning I would wake up to something new to address, and a difficult situation of a sick student, their sick family, or students' mental health or physical health and wellbeing difficulties. Difficulty traveling abroad to get home to parents. students distressed and in quarantine. This was an additional 5-7 hours of work per week + the stress of having so many distressed students to care about and look after. Similar sentiments were expressed by ‘Sanaa’, “There has been more interaction with students to provide them support as they struggle to manage responsibilities related to their jobs, their families, and graduate study.” Volunteerism and Consultancy Faculty who relied on community-based work either halted activities all together, operated using social distancing, or they leveraged technology to keep their work going. ‘Sydney’ wrote: [The pandemic] had its greatest impact on service to the community. It also had an effect on my research due to lack of access to schools. When we went totally virtual and did not return to campus it was difficult to collaborate with others”. ‘Sarah’ shared her experiences: [I] stopped volunteering at one non-profit because despite the pandemic they went back to in-person activities in Summer 2020. I’m still on the email list and they have had multiple COVID cases and some deaths so I’m sad for them but happy that I quit. The other non-profit I volunteered for pre-pandemic moved everything online. I continued to work for them and though things are harder online we received some PPP relief so are keeping the organization afloat. Across participants, efforts to maintain a working relationship with community partners required that faculty either adopt strategies to get the work done virtualy or the work stopped all together. Recommendations for Policy and Practice The global pandemic resulted in significant shifts to faculty work-life. Most notable was an emphasis on teaching required to support the development of materails and resources for virtual instruction. This shift was augmented by increased service to our students and a challenge of access to the very sites that provide students with internship training concentric to their professional development. This represents a profound shift in faculty workloads at brick and mortar instituitons, particularly at research intensive institutions. The shift in faculty efforts necessary during the pandemic will have profound effects on faculty productivity moving forward. For faculty who transitioned to new institutions during the 2019-2020 academic year or who were probationary faculty during the pandemic, the disruptions likely impeded their ability to establish or maintain community-based research projects. If the cornerstone of SoTL are student internships, when the pandemic abated many faculty had to rebuild rapport with internship sites amidst concerns for the health and wellbeing of their students. All aspects of faculty work life changed as a result of the pandemic. In a post-COVID society, the challenges facing the most marginalized students in our nation’s schools were exacerabted. Disparities in access to resources to maintain continuity of instruciton, like differences in access to quality health care and nutricious food, have widened the gap in student achievement. Now is when community-engaged researchers are most needed to bridge the gap between theory and professional practice. Bibliography Boyce, M., & Aguilera, R. J. (2021). Preparing for tenure at a research-intensive university. BMC Proceedings, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-021-00221-8 Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Jossey Bass. Chronicle of Higher Education. (2020, October 1). Here’s our list of colleges’ reopening models. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www-chronicle-com.libalasu.idm.oclc.org/article/heres-a-list-of-colleges-plans-for-reopening-in-the-fall/ Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. Crow, R., Cruz, L., Ellern, J., Ford, G., Moss, H., & White, B. J. (2018). Boyer in the middle: Second generation challenges to emerging scholarship. Innovative Higher Education, 43(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-017-9409-8 Darby, F. (2020, June 16). Sorry not sorry: Online teaching is here to stay. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www-chronicle-com.libalasu.idm.oclc.org/article/sorry-not-sorry-online-teaching-is-here-to-stay Fischer, K. (2020, February 26). Colleges brace for more-widespread outbreak of Coronavirus. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Hardré, P., & Cox, M. (2009). Evaluating faculty work: Expectations and standards of faculty performance in research universities. Research Papers in Education, 24(4), 383–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520802348590 Hutchings, P., & Shulman, L. S. (1999). The scholarship of teaching: New elaborations, new developments. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 31(5), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091389909604218 Jamali, A. R., Bhutto, A., Khaskhely, M., & Sethar, W. (2022). Impact of leadership styles on faculty performance: Moderating role of organizational culture in higher education. Management Science Letters, 12(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2021.8.005 Lake, P. (2021, August 25). How to adjust your employment policies for the COVID Era: Tips for avoiding a legal quagmire. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www-chronicle-com.libalasu.idm.oclc.org/article/how-to-adjust-your-employment-policies-for-the-covid-era McMurtrie, B. (2020a, April 16). The next casualty of the Coronavirus crisis may be the academic calendar. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www-chronicle-com.libalasu.idm.oclc.org/article/the-next-casualty-of-the-coronavirus-crisis-may-be-the-academic-calendar/ McMurtrie, B. (2020b, May 5). Are colleges ready for a different kind of teaching this fall? The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www-chronicle-com.libalasu.idm.oclc.org/article/are-colleges-ready-for-a-different-kind-of-teaching-this-fall/ National Education Association. (2020). All hands on deck: Guidance regarding reopening school buildings. Vega, L. R., & Hengartner, C. J. (2021). Preparing for tenure and promotion at PUI institutions. BMC Proceedings, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-021-00219-2 Vogt, W. P., & Johnson, R. B. (2016). The SAGE dictionary of statistics and methodology: A nontechnical guide for social sciences (5th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

0 Comments

|

AuthorsDr. Kimberly L. King-Jupiter Sharonda Phelps

Doctoral Program in Educational Leadership, Policy & Law Alabama State University, Montgomery, AL, USA Alethea F. Hampton

Alabama State Department of Education, Montgomery, AL USA Brenda I. Gill Department of Criminal Justice and Social Sciences Alabama State University, Montgomery, AL USA Rolanda Horn Department of Institutional Effectiveness Alabama State University, Montgomery, AL USA ArchivesCategories |

- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

RSS Feed

RSS Feed