- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

|

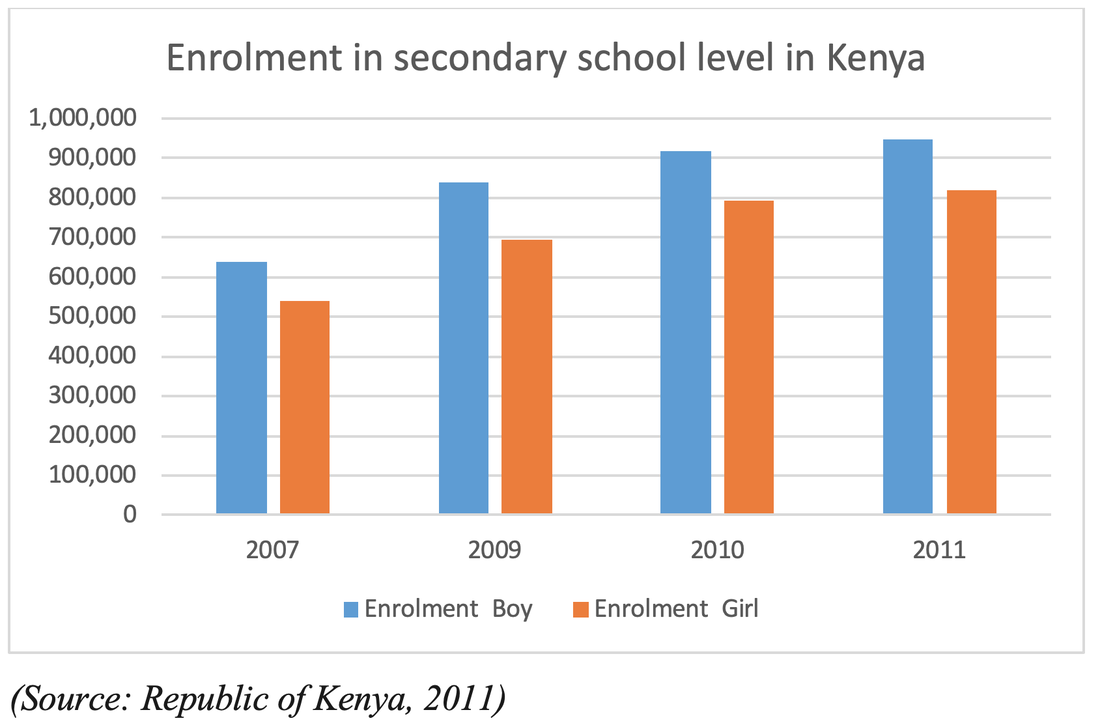

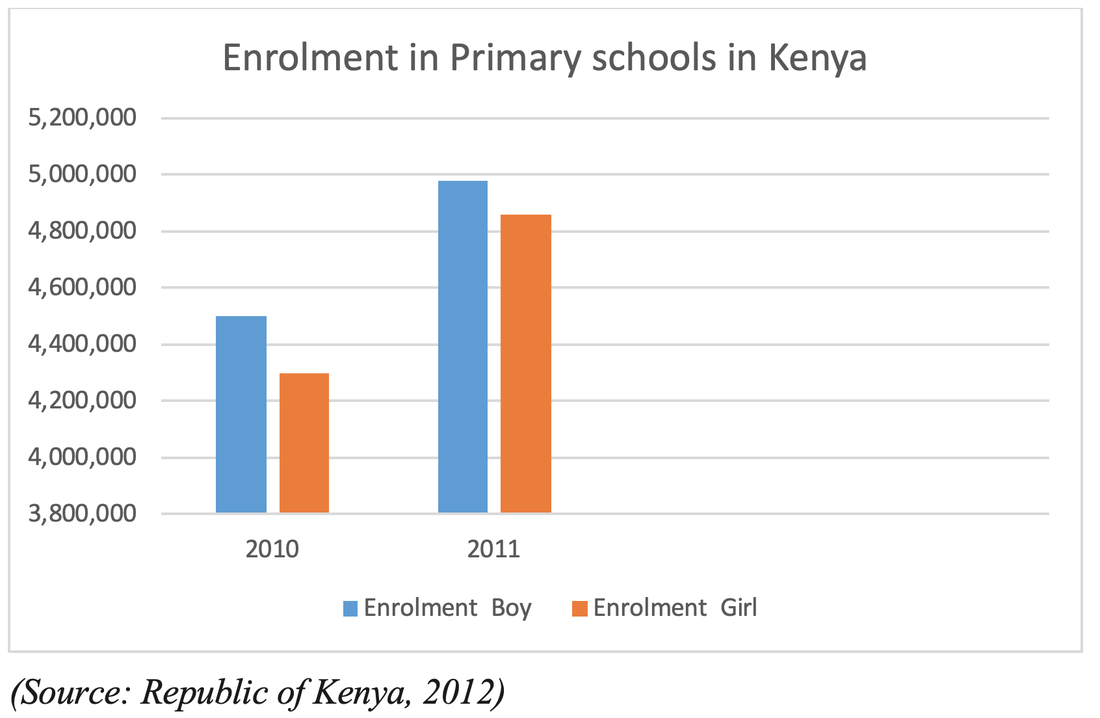

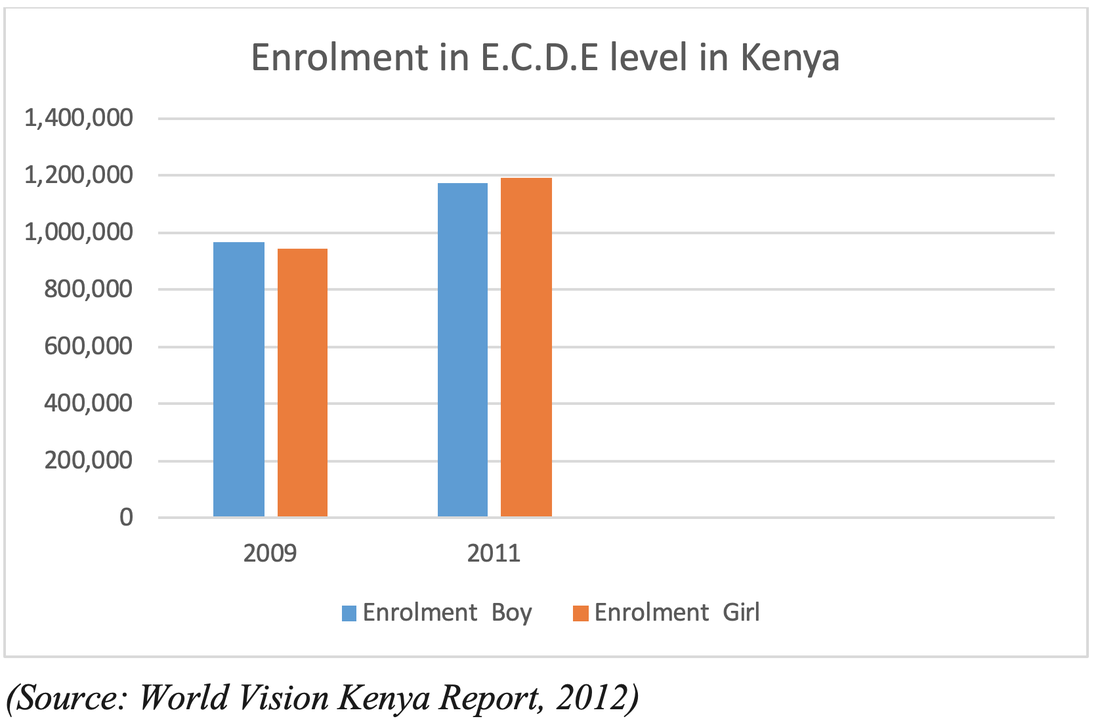

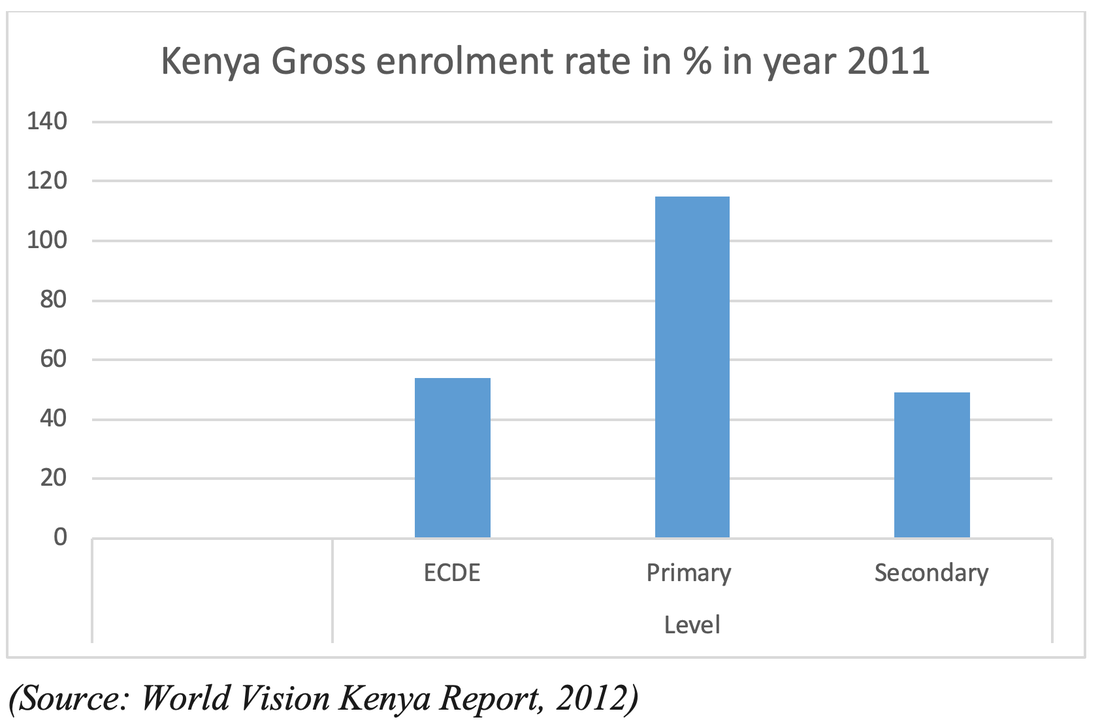

Abstract Accountability in education is a broad concept that could be addressed in many ways, such as using political processes to assure democratic accountability, introducing market-based reforms to increase accountability to parents and children, or developing peer-based accountability systems to increase the professional accountability of teachers. There are various models and forms of accountability in education. School accountability is the process of evaluating school performance on the basis of student performance measures which is increasingly prevalent around the world. Kenya has not been left behind. This paper seeks to explore the challenges and strategies of accountability in education in Kenya. The paper is based on review of literature and document review. The documents were obtained from public records (Ministry of Education, in Kenya), personal documents and physical evidence. The analytical techniques were document analysis and content analysis. The literature review, document and analytical analysis established that the Government of Kenya was struggling with many challenges related to accountability in education. These challenges include; enrolment policy, education for individuals with disabilities, staff and performance, quality assurance and standards, management and governance. The study recommends strategies to enhance accountability to include devising performance indicators through the National Education Sector Plan (NESP). There should be concerted efforts among all the education stakeholders to ensure there is accountability in education. Key Terms: Accountability, Indicators of Accountability, Challenges, Strategies Introduction As the economies of nations compete for strong positions within a competitive global market place, many governments have become increasingly interested in the performance of all aspects of their education systems. This trend, coupled with the enormous expenditures that are devoted to education, has also precipitated widespread public requests for higher levels of scrutiny concerning the quality of education. These demands for information about school system performance can only be addressed through the implementation of systematic accountability systems. Historically, the education profession has conformed to the requirements of regulatory or compliance accountability systems (usually based on government statutes), and has also subscribed to professional norms established by associations of educators. However, at the beginning of the 21st Century, accountability systems have also been required to respond to demands that professional performance be judged by the results that have been achieved (Anderson, 2005). Accountability has been an educational issue for as long as people have had to pay for and govern schools. The term covers a diverse array of means by which some broad entity requires some providers of education to give an account of their work and holds them responsible for their performance (Republic of Kenya, 2011). Accountability mechanisms in the education system in Sub Saharan Africa are in their infancy (World Bank, 2008). Models of Accountability in Education A number of models of accountability in education have been developed, chiefly by Kogan (1986), Ranson (1986), Elliot et al. (1981) and Day and Klein (1987). These models illustrate different codes which specify, for example, alternative methods of presenting and evaluating the account. Whilst there are some differences of classification and nomenclature, four main models of educational accountability emerge from the literature: professional, hierarchical, market and public accountability. Challenges to Accountability in Education 1. Enrollment Policy The Education Sector has been making improvements in terms of access to institutions of basic education and provision of services. However, the challenge of attributing learning outcomes to the investment in the sector still remains. The resource investment over the years, both for development and recurrent expenditures would have by now translated into exemplary results at the ECDE, primary and secondary school levels; however this is not the case (World Vision Kenya, 2012) as the following graphs indicate. Figure 1: Enrollment in secondary school level in Kenya At the Secondary School level the enrollment grew from 1.18 million students in 2007 (639,393 boys and 540,874 girls) to 1.5 million (804,119 boys and 695,896 girls) students in 2009 to 1.7 million (916,302 boys and 792,818 girls) students in 2010 and further 1.8 million (948,706 boys and 819,014 girls) in 2011. Figure 2: Enrollment in primary school level in Kenya Figure 2 shows that at the primary school level, enrollments increased from 8.8 million (4.5 million boys and 4.3 million girls) in 2010 to 9.86 million (4.98 boys and 4.86 girls) in 2011. Figure 3: Enrollment in E.C.D.E in Kenya Figure 3 indicates that the enrollment for ECDE increased from 1.914 million children (967,544 boys and 946,678 girls) in 2009 to 2.37 million (1,175,530 boys and 1,194,518 girls) in 2011. Figure 4: Kenya Gross enrollment rate in % in year 2011 Figure 4 specifies that the Gross Enrolment Rate (GER) for ECDE was still at 54 percent in 2011. While at primary level the gross Enrolment Rate was at 115.0 percent while the Net Enrolment Rate was at 95.7 percent in 2011and the GER for secondary level was at 48.8 per cent (51.0 per cent for boys and 46.8 per cent for girls) and the NER was at 32.7 per cent (32.6 per cent for boys and 33.1 per cent for girls) in 2011.

2. Education for Individuals with DisabilitiesWhile Kenya government recognizes the need to educate all children, including those with exceptional needs, there lacks a mechanism to ensure and oversee that all students have equal access to education. An estimated 80 percent of all individuals with disabilities reside in isolated areas in developing countries (Oriedo, 2003) with 150 million of them being children (Eleweke & Rodda, 2002). Disability-related issues affect approximately 50 percent of the population in these countries (Oriedo, 2003, Mukuria, Korir & Andea, 2007). In most cases, disability problems are compounded by the fact that most of the people with disabilities are extremely poor and live in areas where medical and educational services are not available (Eleweke & Rodda, 2002; Meja-Pearce, 1998; Oriedo, 2003; Mukuria & Korir 2006). According to the 2009 census, this group makes up approximately 20percent of the Kenya's population (Kenya Bureau of Statistics, 2009); unfortunately, only 2percent of individuals with disabilities receive any form of special education (Eleweke & Rodda, 2003; Mukuria & Korir, 2007). 3. Staffing and Teacher Performance: Though the outcry on teacher shortage continues to be heard, additional concerns also revolve around teacher distribution with allegations of some schools having more teachers than they require while in other schools, some classes remain untaught because of teacher shortage. Teachers’ absenteeism also remains an issue that cuts across many schools in the country with concerns that some teachers chose to be away based on a mutual agreement with the head teacher as opposed to an official documentation of leave of absence (World Vision Kenya, 2013). 4. Quality Assurance and Standards support: Teacher performance records are lacking in many schools: While at the classroom level, it is not easy to determine the extent to which the teachers are delivering the right content; but instead the performance of the teacher is left to be reflected in the performance of the learners often during external examinations (Republic of Kenya, 2011). Another critical gap is that the school terms often begin with the teachers not aware of the specific dates that the QASOs would be visiting their schools. The criterion that determines which schools to be visited during a particular term is also not readily available. Some schools also indicate that one calendar year ends without any QASO visiting their schools and as such no quality assurance support is received from MoE throughout the year. Most of the QA&SO are not clear on the kind of support teachers require and they also have capacity gaps (World Vision Kenya, 2013). Even though feedback is given to the schools after visits have been conducted by MoE officials, the feedback never trickles down to the learners and their parents / guardians. Most of the time the feedback is discussed at the teachers level while other actors in education service provision are left out. The feedback at times reaches the headquarters of MoE but there are no clear mechanisms of responding to such feedback until a crisis emerge (World Vision Kenya, 2013). 5. Management and Governance: While some schools have School Management Committees and Board of Management in place, that have undergone trainings conducted by Ministry of Education officials, the functioning of these committees is not reflected in the manner in which school programmes and activities are implemented. In some instances, the head teachers continue to make decisions by themselves and the SMC & BoM members hardly question such decisions. There is also lack of school development plans in most schools and this creates an opportunity for poor plans (Transparency International, 2010). The information on the funds received that is displayed on the school notice boards has been limited to the FPE funds with many head teachers not displaying any other funds the school receive, especially those collected from parents towards other programmes, for example the School Feeding Programmes (SFP). In terms of purchases of school items, there have been outcry among parents that some head teachers collude with suppliers to increase the prices of goods with the aim of receiving “kickbacks.” (Republic of Kenya, 2012). Very few schools do generate annual financial reports for discussion with parents; majority of schools choose to discuss the financial reports with the MoE officials and ignore the parents, guardians and children. In addition, auditing of the funds that the schools receive every year is irregular and such audit reports are never shared with the parents, guardians and children (World Vision Kenya, 2012). 6. Access to Information: Information flow between the school administration and the teachers is another gap that exists in many primary and secondary schools. For instance, some teachers are only aware of the data in regards to the learners in the school and their performance but have no idea on the resource requirements of their schools and the management of resources that the schools receive. The level of awareness of some teachers in regards to various policies and guidelines in education service provision is also minimal; this is however attributed to lack of access to such documents at the school level; there are cases where the school head teachers limit such information to themselves and do not share with the other teachers in the school (World Vision Kenya, 2012). While the children are aware that the government has been financing the Free Primary Education, many of them are not aware of how much they have been entitled to over the years. Worse is the fact that some of the parents and guardians too are not aware of what their children are entitled to under the FPE programme. This is attributed to lack of clear communication modes between the school administration and the children, and their parents and guardians (Republic of Kenya, 2012). 7. Holistic Focus on Learners: On an annual basis, the schools over concentrate on discussing the performance of the children in regard to KCPE and KCSE results; and very minimal is discussed in reference to performance of the children at other levels (class 1 – 7& Form 1-3). While many of the school teachers are aware that some of the learners do not transit to secondary schools, it appears that majority of the teachers have no role in following up where such learners go to. (Transparency International, 2010). Some parents have also left their children in the hands of teachers and do not care to follow up on what their children do in school (Transparency International, 2010). 8. Finances: Though the government supports the Free Day Secondary Education (FDSE) programme, there is a general feeling among the public that secondary education in Kenya is largely expensive. The fact that various categories of schools charge different amounts of fees is something that continues to amaze the public and the government does nothing (World Vision Kenya (2012). Various secondary school heads continue to incur exorbitant expenditures with completely no oversight. For instance who pays for the cost of Kenya Secondary Schools Heads Association Annual meeting? This is something that the public is seeking for accountability on the part of the government. Secondary schools in Kenya continue to manage millions of shillings annually; but majority of the schools do not report to the students, parents and guardians on their incomes and expenditure on annual basis. Reports that are shared publicly are largely in regards to performance and very minimal information on finances. A part from the details of the fees to be paid in the subsequent year, the secondary schools heads often give very minimal information on the expenditure of the previous years (Transparency International, 2010). 9. Public Participation: Even though various districts have a culture of annual education stakeholders meetings, the participants in such meetings are often limited to head teachers, teacher unions, FBOs and NGOs. Public participation in such meetings, for example through the chairpersons of schools and other representatives of parents and children continue to remain very minimal (World Vision Kenya, 2013). Strategies towards Accountability in Education According to World Bank Report (2009) the pressure for compliance with accountability measures comes through an increasingly wide range of mechanisms. The most common are legal requirements. Usually inscribed in higher education law, ministerial decrees, and public sector regulations, these requirements encompass aspects of financial management (e.g., budget documents, mandatory financial audits, publicly available audit reports), quality assurance (e.g., licensing, accreditation, academic audits), and general planning and reporting requirements). The National Education Sector Plan (NESP) 2013-2018 is an all-inclusive, sector-wide programme whose prime goal is: Quality Basic Education for Kenya's Sustainable Development. The sector plan builds on the successes and challenges of the Kenya Education Sector Support Programme (KESSP), 2005-2010. Sector governance, management and accountability in a decentralized setting with devolved responsibilities and diverse partnerships have been emphasized. Clear guidelines for coordination, transparency, and reporting at the national, county, sub-county and institutional levels are paramount. The focus on improvement of education quality specifically targets: improvement of schooling outcomes and impact of the sector investment; development of relevant skills; improved learning outcomes; and improved efficiency and effectiveness in use of available resources (Republic of Kenya, 2015). Mbiti (2016) found out that much of research in developing countries seems likely to move toward using technology to deliver content, as well as to monitor teachers, students, and funding in order to improve accountability. In particular, finding ways for technology to allow instruction to be tailored to the student’s level could dramatically improve the productivity of the education system. According to World Bank (2008) states decentralization to Schools can lead to greater accountability in education. Comprehensive School Reform (CRS) or whole-school reform seeks to overhaul the school system by aligning policies and practices with a coherent central vision to improve public primary and secondary education; Shared Decision-Making (SDM) approaches to school reform aim to empower teachers (Coffey and Lashway 2001). Hallak and Poisson (2006) points that as far accountability in tertiary education is concerned the basic responsibility of the state is to establish and enforce a regulatory framework to prevent unethical, fraudulent, and corrupt practices in tertiary education, as in other important areas of social life. Demand-side financing mechanisms can also be used to promote greater accountability. In the 60 plus countries that have a student loan system, financial aid is often available only for studies in bona fide institutions, that is, universities and colleges that are licensed (at the minimum) or even accredited (Salmi and Hauptman 2006). Conclusion The Government of Kenya is encountering many challenges as it deals with accountability in education owing to the fact that the idea of accountability has not yet been embraced fully neither by the assessors nor those being assessed. Mechanisms have been formulated to enhance accountability but have not yet been implemented fully. Recommendation There should be concerted efforts among all the education stakeholders to ensure thereis accountability in education. There is also needs sensitization about accountability in education as many stakeholders are not aware of their role as far as accountability is concerned. Follow up measures on accountability should be to put in place. References Anderson A.J. (2005). Accountability in Education. The International Academy of Education (IAE) and the International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP). Becher, T., M. Eraut & J. Knight. (1981).Policies for educational accountability. London: Heinemann Educational. Catherine M. F. &Jennifer, L. (2002). Changing Forms of Accountability in Education? A Case Study of LEAs in Wales, Public Administration,77(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00155 Coffey, E., and L. Lashway. 2001. “Trends and Issues: School Reform.” Abstracts, Clearinghouse on Educational Policy and Management. Oregon: College of Education, University of Oregon. Retrieved July 15, 2006 from cepm.uoregon.edu/trends_issues Day, P. and R. Klein. (1987). Accountabilities: Five public services. London: Tavistock Eleweke, C. J., & Rhoda, M. (2000).The challenge of enhancing inclusive education in developing Countries. International Journal on Inclusive Education, 6 113-126. Elliot, J., D. Bridges, D. Ebutt, R. Gibson and J. Nias. (1981). School accountability. London: Grant McIntyre. Farrell, M.C &Law,J.(2002). Changing Forms of Accountability in Education? A Case Study of Leas in Wales. Public Administration77, 2 .Wiley online library. Hallak, J., & Poisson, M. (2005). Ethics and corruption in education: an overview. Journal of Education for International Development, 1(1). Retrieved Month Date, Year, from http://equip123.net/JEID/articles/1/1-3.pdf [accessed Aug 23 2018]. Kogan, M. (1986). Educational Accountability. An analytic overview. London: Hutchinson. Korir, J. & Mukuria, G. & Andea, B. (2007). Educating children with emotional and /or emotional Disabilities in Kenya. A right or a privilege? Journal of International Special Needs Education, 10, 49- 57. Figlio, D & Loeb, S.(2011). School Accountability. In Eric A. Hanushek, Stephen Machin, and Ludger Woessmann, editor: Handbooks in Economics, Vol. 3, The Netherlands: North-Holland, pp. 383-421. Mbiti, M.I. (2016) The Need for Accountability in Education in Developing Countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3) 109–132 Meja-Pearce, A. (1998). Disabled Africa: Rights not welfare. Index on Censorship, 27, 177- 195. Oriedo, T. (2003). The state of persons with disabilities in Kenya. Council for Exceptional Children: Division of International Special Education and Services.From http//www.cec.sped.org/ind/natlover.html. Ranson, S. (1986). ‘Towards a political theory of public accountability in education’, Local Government Studies 4, 77–98. Republic of Kenya (2015). Ministry of Education, Science and Technology National Education Sector Plan Volume One: Basic Education Programme Rationale and Approach 2013 – 2018. Republic of Kenya (2012). The Report of the Task Force on the Realignment of the Education Sector to the Constitution of Kenya. Republic of Kenya (2011) Education Sector Report Republic of Kenya (2012) Education Sector Report Republic of Kenya (2011). Education Sector Report Republic of Kenya (2012). Education Sector Report Richard M. Ingersoll & Gregory J. Collins (2017) Accountability and control in American schools, Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49:1, 75-95, DOI: 10.1080/00220272.2016.1205142 Salmi, J. & Hauptman, M. A.(2006). Innovations in Tertiary Education Financing: A Comparative Evaluation of Allocation Mechanisms. Education Working Paper Series No.4. Washington D.C. Transparency International (2010). The Kenya Education Sector Integrity Study Report Walker, P. (2002). Understanding Accountability: Theoretical Models and their Implications for Social Service Organizations.Social Policy and Administration, 46(1). ISSN 01445596 World Bank (2008). Governance, Management, and Accountability in Secondary Education in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Working Paper no. 127.Washington D.C. World Vision Kenya, (2012). Enhancing Responsiveness and Effectiveness of Basic Education Service Delivery in Kenya Project Reports

1 Comment

|

AuthorDr. Daniel K. Gakunga &

Dr. Reuben Nguyo Lecturer Catholic University of East Africa ArchivesCategoriesKenya Dancers Image Attribution: By Louisa Kasdon (website) [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons |

- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

RSS Feed

RSS Feed