- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

|

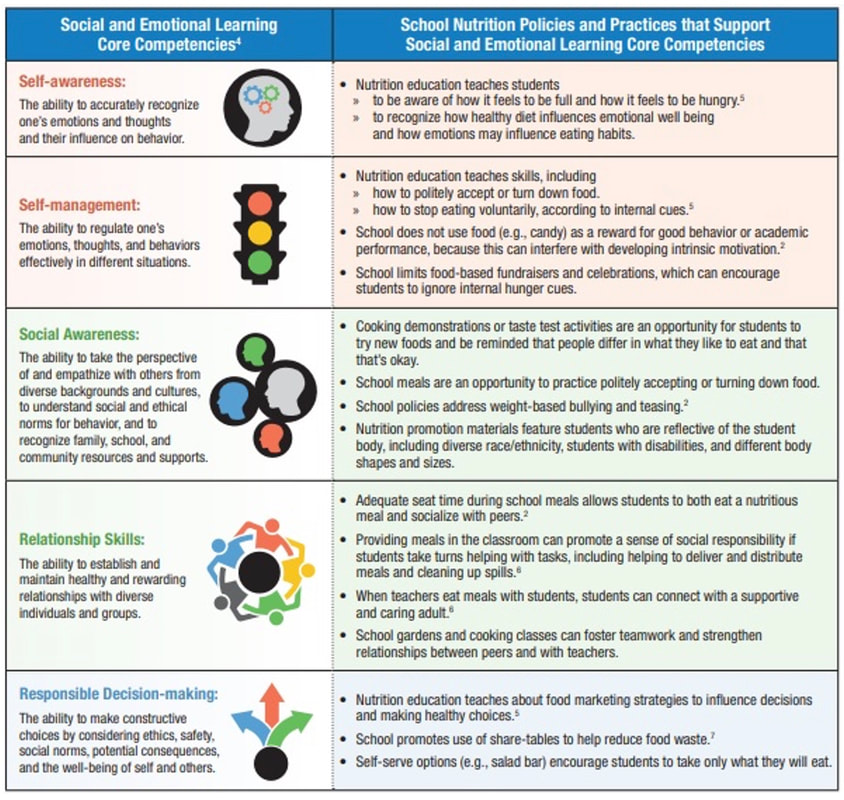

Abstract Adolescence is a transitional phase of growth, learning, self-discovery, and possibility, and a period when behavioral and health issues can begin or worsen, with long-term effects. Poor eating habits can contribute to these issues. Previous research has found that well-structured SEL programs are linked to positive social, enthusiastic, behavioral, and academic outcomes for children and adolescents. We are interested in how Social Emotional Learning (SEL) links to adolescent eating behaviors. We begin with a short review of key studies on school-based programs aiming at enhancing social and emotional learning and student development, with a focus on SEL and adolescent diet research. Next, we developed four research questions to guide us. We found answers to part of the research questions in the literature. The remaining questions were addressed using a framework and a report on best practices for promoting adequate nutrition in schools for adolescents. The literature suggests that SEL programs are associated with positive outcomes such as improved attitudes toward oneself and others, increased altruistic behavior, reduced behavioral dysfunctions and mental distress, and improved academic accomplishment. Furthermore, a meta-analysis study involving a large sample size of students showed improved SEL ability, attitudes, and good social behaviors, as well as significant improvements in academic achievement. We also identify gaps in the extant literature that hinder insight into SEL and emotional eating behavior (change) during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Presently, the evidence on SEL and diet is insufficient to effectively address adolescent nutrition issues. We conclude that more focused studies with primary data on the association between SEL and emotional eating in adolescents are needed. Keywords: Adolescence, behavior change, SEL program, growth, emotional eating, emerging adulthood, and eating habit. Introduction Adolescence is a transitional phase of growth, learning, self-discovery, and possibility. Puberty marks the start of adolescence and ends when a person acquires a self-sufficient role in life (Damon, 2004). It is a period of rapid social and emotional development for young people, during which they undergo some of the most profound brain changes since childhood (Hagan et. al., 2019). This transition stage presents a once-in-a-lifetime chance to make a meaningful contribution to the prospects and well-being of young people. During adolescence, young people's identities evolve as they form bonds with friends, endure rejection, and seek participation in groups. It is also a time when behavioral and health issues can begin or worsen, with long-term effects (Yeager, 2017). Some of these problems can stem from poor eating habits and low Social Emotional Learning (SEL). We were interested in learning more about students’ eating habits and reasons for eating, and how students’ diets might connect to SEL. This paper starts with a review of several studies of school-based programs aimed at promoting social and emotional learning and student development. It then specifically turns attention to any literature on SEL and adolescent diet. The Current Research and Research Questions The emergence of new research in SEL and the importance of the topic led us to four distinct research questions to guide this paper: (1) Do SEL programs have a noticeable impact on adolescents’ general wellbeing? (2) Does SEL programming imbibe skills in adolescents that will make the process of transition to adulthood successful? (3) Is there literature on, and are there adolescence SEL programs aimed at improving students’ diets? (4) How can SEL programs promote healthy eating habits among adolescents? We found answers in the literature to the first two questions. And we found a framework and a paper on best practices on how to promote good nutrition in schools for adolescents that addressed parts of questions 3 and 4. However, we found very little else in the literature to answer in full the last two questions. Defining SEL The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) defines (SEL) as “the process through which children and adults understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.” SEL is defined by O’Conner et. al. (2012) as the process by which children and adults learn to understand and manage emotions, maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions. SEL programs have the potential to prevent adolescent eating disorders. Yeager (2017) asserted that SEL programs aim to improve adolescents’ abilities and mindsets to help them cope with their problems more effectively. He further stated that SEL programs aim to improve skills and mindsets in adolescents to help them cope more successfully with their problems and build respectful school environments that young people want to be a part of. Social-Emotional Learning and Adolescent Overall Wellbeing, Prosocial Behavior, and Self-Awareness, and Academic Success: The Recent Literature Previous studies revealed that well-structured SEL programs are closely related to favorable social, enthusiastic, behavioral, and scholastic results for children and adolescents (Durlak et al., 2011). A review of the literature of SEL research showed that most of the successful interventions took place in the United States of America (Harlacher and Merrell, 2010; Durlak et al., 2011). These reviews usually include some school-based, universal SEL program evaluations as well as a variety of additional treatments aimed at improving academic performance (Wang, Haertel, & Walberg, 1997; Zins et al., 2004), aggressive and antisocial behavior (Losel & Beelman, 2003; Wilson & Lipsey, 2007), or positive youth development (Catalano et al., 2002). Other studies show findings on the promotion of equal personal relationships, classroom-based SEL program, SEL and the power of relationship/mentoring, SEL and youth development, SEL and extracurricular variables, and SEL and interactive mobile technology (Hagan et. al. 2019; Green et. al. 2020; Gannon 2017; Portela-Pino et. al. 2021; Cherewick et. al. 2021). However, our literature review revealed very little on the relationship between adolescence SEL and diet. According to the findings from the reviewed literature, SEL programs are linked to good outcomes such as enhanced attitudes toward oneself and others, increased altruistic conduct, reduction in behavioral dysfunctions and mental anguish, and better academic achievement (Catalano et al., 2002; Zins et al., 2004). According to (CASEL, 2021), well-implemented, evidence-based SEL programs improve academic achievement, behavior, and provide a high return on investment. In a meta-analysis study involving a large sample size of 135,396 students by Durlak et. al. (2011), students displayed improved SEL abilities, attitudes, and good social behaviors, as well as significant improvements in academic achievement. Durlak et. al (2011) therefore concluded that SEL programs in schools had large positive mean effects on several skills, attitudes, behaviors, and academic achievements. At all levels of education, social-emotional programs are directly linked to improved academic achievement (Keltner, 2020). Taylor & Dymnicki, 2007 in their book titled "empirical evidence of social and emotional learning's influence on school success" noted a significant improvement in the academic performance of pupils from kindergarten through high school. Rutledge et al. (2015) investigated the academic disparities between two low-performing and two high-performing schools. Even though the demographics were identical, the results were strikingly different. The findings revealed that the higher-performing schools had strong academic and SEL programs and practices while the school without SEL programs lagged behind. Ross and Tolan (2018) analyzed longitudinal data from the Study of Positive Youth Development by adopting the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) framework. They first tested and validated the SEL factor model using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in a standardized sample of 1,717 5th grade students in the United States. The model was subsequently tested for longitudinal measurement invariance using CFA models that included 6th and 7th-grade students to ensure that SEL was a reliable model. The validity of the SEL model was further demonstrated by the students' remarkable academic achievement. Conclusively, the findings support the use of a slightly modified version of the CASEL model as an alternative framework for adolescent research and practice. Concerned about the difficulties adolescents encounter while growing up such as unwanted/teenage pregnancy, increased sexually transmitted infections (STDs), and sexual assaults, Ledezma et. al. (2020) used the SEL program as a probable pedagogy for facilitating the development of adolescents’ social-emotional skills and capabilities in the direction of equality in gender, roles, and rights. The study described the process of development and planning to surround the implementation and evaluation of the SEL intervention for middle school students (aged 12 – 15 years) in Panama using the Intervention Mapping Protocol for children. The authors concluded that Intervention Mapping enables the investigation of numerous elements impacting the development and implementation of Social Emotional Learning programs in the Bottom Billion that enhance egalitarian interactions among adolescents. This aspect of the research done by Ledezma et. al. (2020), is contrasted by Yeager (2017), who stated that (SEL) programs are one way to help them navigate the difficulties encountered by adolescents in their formative years. The programs were targeted at eradicating teenage pregnancy, youth violence, and smoking. On the positive side, Yeager believes that an effective universal SEL program can improve the lives of teenagers, but the SEL program has little or no effect on middle adolescents (roughly age 14 to 17 years). In another study conducted, Green et. al. (2020) explored the effectiveness of a classroom‐based SEL program for middle school students (ages 10 – 13 years). The study took place in two middle schools in Florida with a sample of 2,740 students. The researchers were attempting to determine the effectiveness of a specific SEL preteen mentoring curriculum called the Speaking to the Potential, Ability, and Resilience Inside Every Kid (SPARK). The authors suggested that strengthening the behavioral and emotional skills of students through students centered SEL programs is a significant way of supporting healthy growth and avoiding negative consequences among young people. The results showed that the SPARK curriculum influenced the academic performance of students that were exposed to it when compared to the comparison group. These results are consistent with the work of Corcoran, Cheung, Kim, and Xie (2018) that SEL had a positive effect on reading, mathematics, and science compared to traditional methods, consistent with previous reviews. While much has been published on SEL and overall wellbeing, prosocial behavior, self-awareness, and academic success, our literature review found very little on the relationship between adolescence SEL and diet. Adolescents and Eating People often turn to food when they are under stress, lonely, sad, anxious, or bored; only a few people make the connection between eating and feelings (Gavin, 2018). A Pew Research Center (PRC) report (2016) showed that unhealthy eating habits are the major problem for most Americans in recent times; one of such problems is obesity. The study conducted by Deforche et. al. (2015) revealed that changes in eating behavior (such as increasing snack consumption, missing breakfast regularly, and consuming fewer fruits and vegetables) have been proven to be the major cause of obesity in American adolescents and adults. Students who participate in school breakfast and lunch programs are more likely to attend class, are emotionally healthier, and are less likely to abscond themselves from school. The importance of adolescent nutrition for their immediate and future health cannot be overstated. Lassi et. al, (2017) opines that the reasons for adolescent nutritional inadequacies are multi-faceted, with impacts at the individual, family, and population levels all playing a role. A Framework and Best Practice for Promoting Good School Nutrition Center for Disease and Control (CDC), United States Department of Health and Human Services developed a framework for describing the relationships between the school nutrition environment, the social and emotional climate (SEC), and activities that enhance students' social and emotional learning (SEL). Figure 1: CDC Framework The table below lists SEL basic competencies and examples of school nutrition policies and practices that reflect them. Table 1: CDC SEL core competencies The best practice, according to Partners for Breakfast in the Classroom (PBC, 2010), demonstrates how SEL can be integrated into breakfast in the school and the benefits that can result. By bringing breakfast into the classroom and incorporating it into the school curriculum, students have access to a nutritious and healthy breakfast. Students are always learning, even while eating breakfast. Breakfast in the classroom can support SEL by contributing to a pleasant social atmosphere, strengthening staff-student relationships, and assisting students in the development of soft skills (PBC, 2010).

Adolescence Social Emotional Learning and Emotional Eating: A Topic for Further Study It is a well-established fact that nutrition has a strong influence on adolescent achievement, well-being, and behavior. As noted above, adolescents’ diets are important for immediate and future health. Although we found very little about SEL and adolescent diet in our search, we did find a related discussion on diet regarding ‘emotional eating.’ Gavin (2018) asserts that emotional eating occurs when people utilize food to cope with their emotions rather than to satisfy their hunger. Zeeck, Stelzer, Woolfgang Linster, Joos, & Hartmann (2010) categorized emotional eating as disordered eating because it has been associated with inappropriate food choices and binge eating. Their research also established that emotional eating is disordered eating or eating in response to bad emotions or negative affect (Zeeck, et. al., 2010). Lazarevich et al (2016) studied the relationships between depression, emotional eating, and body mass index in young adults. And Sims et. al (2008) discovered that obese and overweight participants said they have been indulging themselves with unhealthy food in reaction to stress and emotional trauma. The anxiety reduction model proposed by Kaplan & Kaplan, (1957) posited that overeating was used to cope with anxiety. Similarly, obese persons frequently eat in response to anger, loneliness, boredom, and sadness (Ganley, 1989). PRC report (2016) affirmed that obesity has become a major public health concern among both children and adults, and there has been a significant increase in public health concerns. While these studies are valuable, they do not directly address questions 3 and 4 regarding the relationship between adolescent social-emotional learning and diet. Specifically, are youths eating for the correct reasons? Is there value in sensitizing them on the importance of eating food for the right purpose? What other factors, such as depression are associated with obesity in adolescents? What programs could be designed and tested to shed light on the extent to which this is a problem, and address ways to lessen it? At what time should SEL type interventions be implemented? This gap in the literature, on adolescent emotional eating and SEL, deserves future attention study. Conclusions and Recommendations for Further Study Despite a paucity of data, our review of the literature underlines the importance of studying the relationship between SEL and diet in adolescents. As it stands today, the evidence on SEL and diet is not sufficient to fully address nutrition problems among adolescents. It is our conclusion that more focused studies with primary data are needed. One area, identified above, needs further study is the relationships between SEL and emotional eating in adolescents. It is envisaged that more studies on SEL and diet will help shed light on the best ways to promote healthy eating and boost the well-being and academic success among adolescents. References “School Nutrition and the Social and Emotional Climate and Learning.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 21 Sept. 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/nutrition/school_nutrition_sec.htm “School Nutrition SEL - Centers for Disease Control.” CDC, Centers for Disease Control, https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/nutrition/pdf/321123-A_FS_SchoolNutrition.pdf “What Does the Research Say?” (2021). CASEL, https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-does-the-research-say/ Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A. M., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2002). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Prevention & Treatment, 5, Article 15. doi: 10.1037/1522- 3736.5.1.515a Cherewick, M., Lebu, S., Su, C., Richards, L., Njau, P. F., & Dahl, R. E. (2021). Study protocol of a distance learning intervention to support social emotional learning and identity development for adolescents using Interactive Mobile Technology. Frontiers in public health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.623283 Corcoran, R. P., Cheung, A. C. K., Kim, E., & Xie, C. (2018). Effective universal school‐based social and emotional learning programs for improving academic achievement: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of 50 years of research. Educational Research Review, 25, 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.12.001 Damon, W. (2004). What is positive youth development? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 13-24. Deforche, B., Van Dyck, D., Deliens, T., & Bourdeaudhuij D. (2015). Changes in weight, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and dietary intake during the transition to higher education: A prospective study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. 12 (16). Durlak, J., Weissberg, R., Dymnicki, A., Taylor, R., & Schellinger, K. (2011). The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Society for Research in Child Development, Inc. 82(1), 405-432 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x Ganley RM. Emotion and eating in obesity: A review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1989;8:343–361 Gannon, N. (2017). Social-emotional learning and wellness: A mindful bridge supporting youth development. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from http://www.actforyouth.net/resources/stya/webinar-stya-sel-0118.pdf Gavin, M. L. (2018). Emotional eating (for teens) - nemours kidshealth. KidsHealth. Retrieved November 10, 2021, from https://kidshealth.org/en/teens/emotional-eating.html Green, A. L., Ferrante, S., Boaz, T. L., Kutash, K., & Wheeldon-Reece, B. (2021). Social and emotional learning during early adolescence: Effectiveness of a classroom‐based SEL program for middle school students. Wiley Online Library. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pits.22487 Hagan, D., Sánchez, B., Cascarino, J., & White, K. (2019). Social and emotional development in early adolescence. Mentor. Retrieved November 7, 2021, from https://www.mentoring.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Social-and-Emotional-Development-in-Early-Adolescence-Tapping-into-the-Power-of-Relationships-and-Mentoring.pdf Harlacher, J. E. and Merrell, K. W. (2010) Social and emotional learning as a universal level of student support: Evaluating the follow-up effect of strong kids on social and emotional outcomes. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26, 212–229 Kaplan, H. I., & Kaplan, H. (1957). The psychosomatic concept of obesity. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 125, 181–200 Keltner, K. (2020). The effects of social-emotional learning at the secondary level. NWCommons. Retrieved November 6, 2021, from https://nwcommons.nwciowa.edu/education_masters/243/ Lassi, Z. S., Moin, A., Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2017, April 24). NYAS Publications. The New York Academy of Sciences. Retrieved November 9, 2021, from https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nyas.13335 Lazarevich, I., Camacho, M. E. I., Velázquez-Alva, M. del C., & Zepeda, M. Z. (2016). Relationship among obesity, depression, and emotional eating in young adults. Appetite. Retrieved November 5, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666316304597 Ledezma, A. B., Massar, K., & Kok, G. (2020). Social Emotional Learning and the promotion of equal personal relationships among adolescents in Panama: A study protocol. OUP Academic. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://academic.oup.com/heapro/advance-article/doi/10.1093/heapro/daaa114/5922855 Losel, F., & Beelman, A. (2003). Effects of child skills training in preventing antisocial behavior: A systematic review of randomized evaluations. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 587, 84–109 O'Conner, R., Feyter, J. D., Carr, A., Luo, J. L., & Romm, H. (2017). A review of the literature on social and emotional learning for students ages 3-8: Characteristics of effective social and emotional learning programs (part 1 of 4). Institute of Education Sciences (IES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved November 7, 2021, from https://ies.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=REL2017245 Partners for Breakfast in the Classroom. (2019). Social Emotional Learning Support. School Nutrition. Retrieved November 9, 2021, from https://schoolnutrition.org/uploadedFiles/10COVID-19/11_Back_to_School/social-emotional-learning-support.pdf Portela-Pino, I., Alvariñas-Villaverde, M., & Pino-Juste, M. (2021). Socio-emotional skills in adolescence. influence of personal and extracurricular variables. MDPI. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/9/4811 PRC. (2016). Public Views about Americans’ Eating Habits. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2016/12/01/public-views-about-americans-eating-habits/ Ross, K. M., & Tolan, P. (2018). Social and emotional learning in adolescence: Testing the Casel model in a normative sample. SAGE Journals. Retrieved November 5, 2021, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0272431617725198 Rutledge, S. A., Cohen-Vogel, L., Osborne-Lampkin, L. T., & Roberts, R. L. (2015). Understanding effective high schools: evidence for personalization for academic and social emotional learning. American Educational Research Journal, 52(6), 1060–1092 Sims, R., Gordon, S., Garcia, W., Clark, E., Monye, D., Callender, C., & Campbell, A. (2008). Perceived stress and eating behaviors in a community-based sample of African Americans. Eating Behaviors, 9, 137-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.06.006 Taylor, R. D., & Dymnicki, A. B. (2007). Empirical evidence of social and emotional learning's influence on school success: a commentary on "building academic success on social and emotional learning: what does the research say?," a book edited by Joseph E. Zins, Roger P. Weissberg, Margaret C. Wang, and Herbert J. Walberg. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 17(2-3), 225–231 Wang, M. C., Haertel, G. D., & Walberg, H. J. (1997). Learning influences. In H. J. Walberg & G. D. Haertel (Eds.), Psychology and educational practice (pp. 199–211). Berkeley, CA: McCatchan Wilson, S. J., & Lipsey, M. W. (2007). School-based interventions for aggressive and disruptive behavior: Update of a meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33(Suppl. 2S), 130–143 Yeager, D. (2017). Social and Emotional Learning Programs for Adolescents. The Future of Children. 27(1), 73-94 Zeeck, A., Stelzer, N., Woolfgang Linster, H., Joos, A., & Hartmann, A. (2010). Emotion and eating in binge eating disorder and obesity. European Eating Disorders Review, 19, 426-437. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1066 Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Wang, M. C., & Walberg, H. J. (Eds.). (2004). Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say? New York: Teachers College Press

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsOlukayode Apata &

Daniel Paintsil School of Education The University of Southern Mississippi USA ArchivesCategories Mississippi River from Fire Point in Effigy Mounds National Monument, Iowa, USA Image Attribution: NPS photo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

RSS Feed

RSS Feed