- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

|

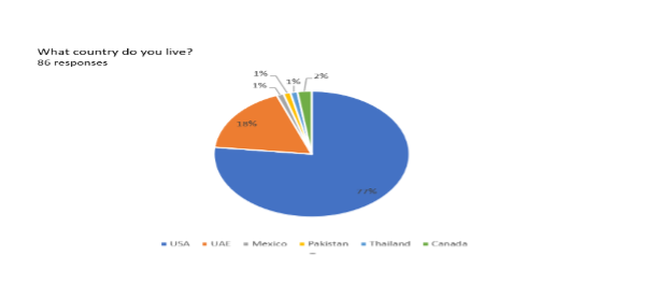

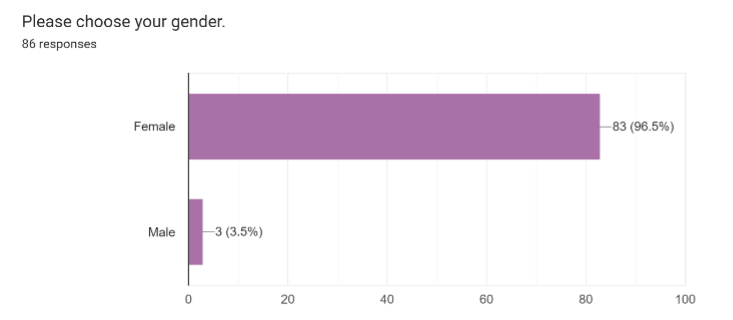

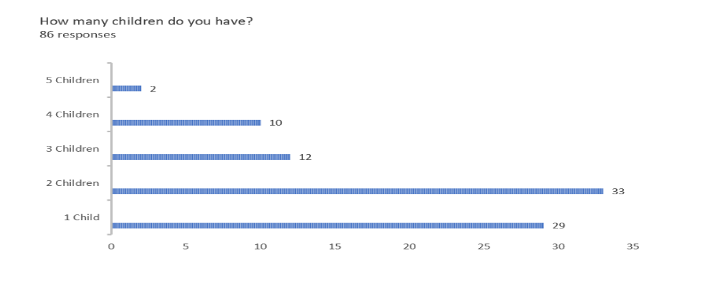

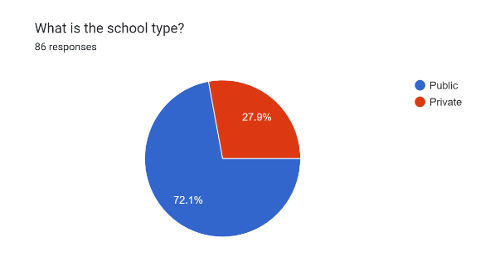

Abstract This mixed-method study examined the parents' perceptions of distance learning during the COVID-19 closure. Three research questions directed the research, and a purposeful sampling technique was applied. A structured online Google Forms questionnaire that contained closed and open-ended questions was posted through Facebook and used as a data collection instrument. The research findings display parents' views about the school, children, and their readiness for distance learning during the pandemic, as the disadvantages and advantages of distance learning. The study gains attention to school leadership to encourage collaboration among the community, schools, and families that had become an essential element during the transfer to online education during the pandemic. Keywords: COVID-19 Closure, Parents' Views, Disadvantages of Distance Learning, Advantages of Distance Learning Introduction According to UNESCO (2020), data, 110 countries declared nationwide school closures by March 16th, 2020, directly affecting 42.3% of children involved in education. By April 20th, 2020, the proportion of affected children had grown to 81.8%, a total of 1,291,004,434 learners in 151 countries. The worldwide closure of schools due to the COVID-19 pandemic obliged parents to accept crucial pedagogical roles for children's education. The virtual world of online education rendered several obstacles for families. This research study intends to explore the parents' beliefs regarding the online education experiences of their children, the problems they have faced, as well as the school support they need. Theoretical Background Parental involvement has been shown to grow academic success and student engagement across all grade levels (Callahan et al.,1998, Fan & Chen,2001). Previous research has emphasized environmental concerns such as parent education and socioeconomic status as factors in levels of this involvement (Li & Qiu, 2018). As those two problems are impossible or hard to change, it is significant to focus on areas practitioners and schools can improve, explore methods of parent involvement, and present what researchers have found as applied technics for developing an accepting environment for 21st Century parents. According to the research, most parents are involved in students' education (Gonzalez-DeHass, 2016; Tatla et al., 2019). However, they do not have the enthusiasm to talk to other parents from the school and make the children's school improve, even though building relationships among parents would increase accountability and social networks. The next theme in the existing research is the quality of family-school relationships. Parents' communication with teachers and teacher attitudes have been seen as significant predictors of activities promoting parental involvement (Fan & Chen,2001; Yang et al.(2022). Schools must support parental participation and cultivate new approaches for this communication to be positive and welcoming since parental behavior and beliefs can nurture a good student achievement climate (Gonzalez-DeHass, 2016; Haskins & Jacobsen, 2017). The literature delivered some ideas regarding successful techniques of parental involvement: (a) parent workgroups; (b) cultural awareness workshops for parents to build ownership within the school (Taddeo & Barnes, 2016). Special school programs can address parents' and teachers' beliefs about the significance of parent-school partnerships. In addition, technology is seen as a new way of communication that might facilitate and support parental involvement (Haslam et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018). Research Methodology Participants The participants in the study were parents of students attending private and public schools (Fig.4). The research contained 86 examinees, of which 96.5% were mothers, 3.5% were fathers (Fig.2) from the USA, UAE, Mexico, Pakistan, Thailand, and Canada (Fig.1) who took over responsibility for children's education during the pandemic closure. Twenty-nine participants reported having one child in the family, thirty-three had two children, twelve had three children, ten had four children, and two had five children (Fig.3). Figure 1. Participants' country Figure 2. Participants' gender Figure 3. The number of children in the participants' families Figure 4. School type Research Questions This research study intents to answer the following questions:

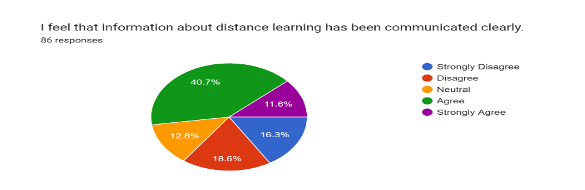

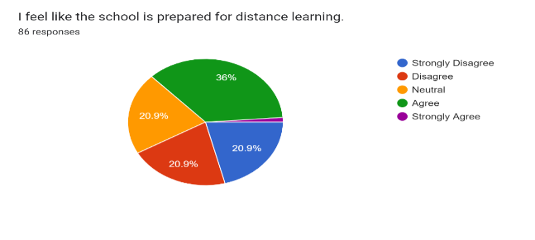

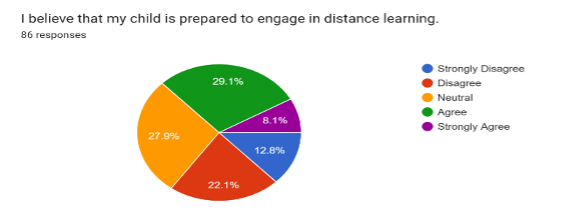

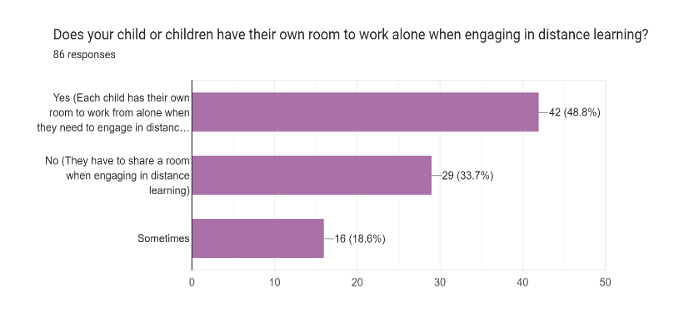

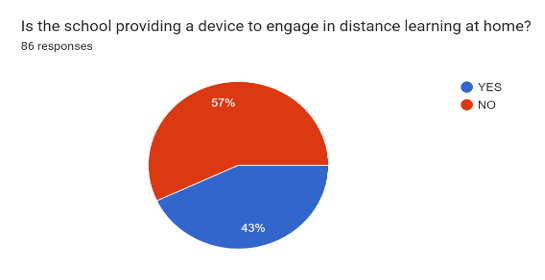

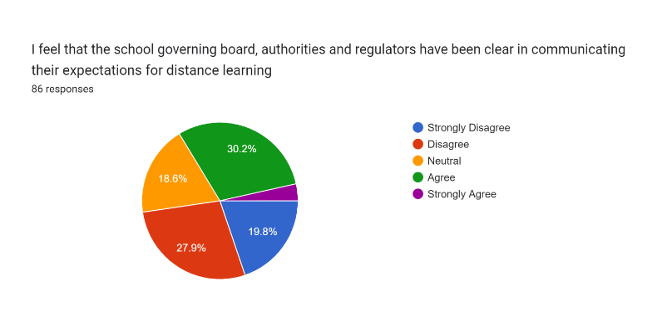

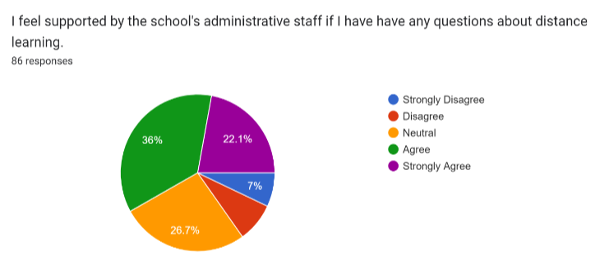

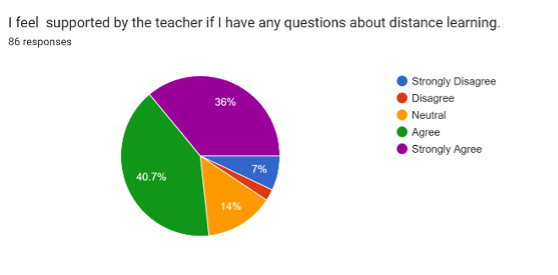

Data Collection Techniques The mixed-method approach collected parents' thoughts about distance learning during the COVID-19 lockdown. The structured online questionnaire created on Google Forms used in the study consisted of four sections based on the study participants' demographic and the abovementioned research questions. The first part was dedicated to the socio-demographic questions; the second portion of the questions comprised a five-level scale on which the parents assessed their agreement with school readiness and support in distance education, parental readiness for distance learning, "yes," "no," and "sometimes" questions on learning space availability, and "yes" or "no" question about the availability of the devices for distance learning. In addition, in the second part, parents described their opinions through open-ended questions. The third and fourth parts included open-ended questions in which parents gave their perspectives on the disadvantages and advantages of distance education. This study displays and interprets the data from analyzing these open-ended questions. The investigation happened during April, May, and June of 2020 and was launched just one month after the beginning of distance learning. A purposeful sampling technique was applied. The questionnaire was published as a Google Form on Facebook, and the post was available to all interested parents of school-age children that were involved in distance learning. Parents from different countries voluntarily contributed to the research study by signing the content form explaining the study aims and objectives at the beginning of the questionnaire. Data Analysis A total of one hundred-four responses were collected, and only eighty-six responses were used for the data analysis. The data analysis was grounded on an inductive thematic study identifying, evaluating, and reporting data themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The quantitative data was assessed with Excel Spreadsheets generated by Google Forms. Findings and Discussions Parents Perceptions About School, Children, and Their Readiness for Distance Learning The answers to the first research question, the parents' perceptions about the school, children, and their readiness for distance learning during COVID were evaluated using the thematic analysis method and emerged three themes: (1) school readiness for distance learning; (2)school support in distance learning; and (3) parental readiness for distance learning. School Readiness for Distance Learning. Figure 5. Schools-parents communication about distance learning Only 40.7% of the parents agreed and 11.6% strongly agreed that information about distance learning had been communicated clearly (Fig.5). 18.6% disagreed, 16.3% strongly disagreed with this statement, and 12.8 % stayed neutral. Some parents mentioned that social media was the only way to learn about distance learning. "Parents were only communicated thru social media, not by school or teachers." About 40% of the parents agreed that schools were prepared for distance education, while the other 40% disagreed; 20.9 % stayed neutral (Fig.6). 29.1 % agreed and 8.1% strongly agreed that their children were prepared to be engaged in distance education; 22.1 % disagreed, 12.8% strongly disagreed, and 27.9 % stayed neutral (Fig. 7). Figure 6. Schools' readiness for distance learning Figure 7. Student's readiness for distance learning Forty-two parents (48.6.%) reported that their children had their own room to work in when they needed to engage in distance education; however, twenty-nine parents (33.7% ) noticed that their kids had to share a room. Sixteen parents (18.6%) said it sometimes happened (Fig.8). 57% of the participants acknowledged that the school did not provide their children with devices for distance learning. In comparison, 43% stated that schools provided computers for the students (Fig. 9). Parents underlined the importance of having specifically school computers with all website restrictions installed. "I believe that it is vital that school districts make the one-to-one laptop a priority for schoolwork. Students who use personal (family) computers lack restrictions from YouTube and other websites where they get distracted." Figure 8. Learning space for distance learning Figure 9. Devices for distance learning All these findings were consistent with the results obtained by Asio and Bayucca (2021), who found that the schools were not ready to employ distance education. Connectivity was their primary concern, as well as teacher and school administration preparation and competencies and funding, and the availability of computer devices for distance education. Moreover, the Francom et al. (2021) survey study examined the obstacles teachers underwent during the COVID-19 closure and the level of administrative support they wished to have. It found that a wide variety of applications and websites familiar to teachers were used for distance learning. Nevertheless, teachers are still faced with several challenges: (a) engaging students and parents; (b) a deficiency of school guidelines; and (c) student computer access and Internet issues. Likewise, investigating the elementary school teacher's readiness to adopt online learning and applying a quantitative approach, Andarwulan et al. (2021) concluded that teachers were not fully ready for the online learning policies implementation due to (a) deficiency of the technology tools, (b) not readiness to adapt technology, (c) lack of money to buy Internet, (d) connectivity issues, and (e) students unreadiness for the online learning mode. Conversely, Palero and Mutya (2022) found that the secondary school science teachers' readiness related to communication and technical skills, time management, and their attitude toward online learning was high. They also faced struggles and many challenges but still developed capabilities for online education. Similarly, Nikolopoulou and Kousloglou (2022) concluded that teachers strongly perceived online education. They emphasized that they provided clear instructions and communications with parents and students while experiencing weak administrative support and disagreement regarding online learning professional development. School Support in Distance Learning. Approximately 34% of the responders admitted that the school governing board and authorities had been clearly communicating their expectations about distance education, while 27.9% disagreed and 19.8% strongly disagreed with this statement; 18.6 % stayed neutral (Fig. 10). Parents emphasized the significance of school support and underlined that it must be consistent across all schools. "I think that districts need to have a uniform way to distribute materials to the students. I have three children in three different buildings in our district, and all the deliveries are different. It makes it very hard for the parents to keep track and support the students in the organization." "... kids need structure, and parents need the support in scheduling so their children/students see a united front!" Figure 10. Schools' expectations of distance learning One of the participants suggested creating a social media platform that would allow everyone to see the latest news and regulations on behalf of distance learning. "I am missing a platform for open discussions with schoolteachers, administrators, and other stakeholders of distance learning." 36% of the parents agreed and 22.1% strongly agreed that they felt supported by the school's administration in case they had any questions on behalf of distance learning, while about 15% disagreed with this statement; 26.7% stayed neutral (Fig.11). Furthermore, about 77% felt supported by the teachers, while around 15% did not feel that way; 14 % stayed neutral (Fig.12). Figure 11. Administration support in distance learning Figure 12. Teachers' support in distance learning Despite multiple studies on educational leadership during the pandemic closure, there is insufficient research on connections between online educational experiences and the perspectives of parents and school leaders during COVID-19 (Lee, 2022). The current study found insufficient communication between school administration and parents regarding online education. Nevertheless, more than 50% of the responders felt supported by schoolteachers and the administration. According to Yang et al.(2022), higher levels of teacher support and parental evolvement are linked to the highest level of student engagement. Parental Readiness for Distance Learning. Figure 13. Parents' support in distance learning

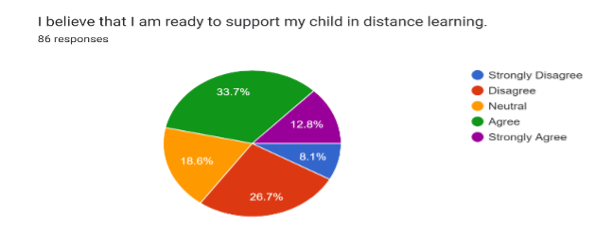

Nearly 47% of the participants believed they were ready to support their children in distance learning; however, about 35% disagreed and 18.6% stayed neutral (Fig.13). They were concerned about the lack of time and qualifications to provide the support needed. "I do not have time to work with my son to give him the education he needs." "I am not educated nor qualified enough to be teaching my children at home." "Working parents cannot work and teach -it is not possible for successful outcomes." "I cannot do what I need to do while dealing with my children's teachers; as well, it is too much for me as a parent." "I realize every one of us, student, parent, teacher, administrator, IT support, and more, are all in these same choppy waters, each in a unique boat. I know our teachers and leadership is working so hard from the other side of the screen and beyond to work through right now and prepare and problem-solve for what is to come. Personally, I am missing it all, but I think it comes down to the lack of preparation for the parent and for the teacher (and that probably stems from a lack of having a plan for something such as this)." These results are similar to Tocalo's (2022) conclusions. The researcher stated that parents appeared ready for the new realities of online education. Though, they indicated the need for (a) pieces of training on distance learning, (b) distance learning skills and knowledge facilitation, (c) adequate internet access, (d) psychological support, (e) teacher scaffolding, and (f) constant teacher-parent communications. Conversely, Alharthi (2023) encountered that "parents would prefer to keep to their chosen role rather than fulfill the teaching role imposed on them by COVID-19" (p.1) and desired more school support (Lau & Lee, 2021). Lack of support from school caused a higher level of psychological distress during online learning (Calear et al., 2022). Disadvantages of Distance Learning The responses to the second research question about the disadvantages of distance learning were also evaluated using the thematic analysis method and emerged seventeen themes. 1. Lack of students' motivation 2. Lack of student focus 3. Lack of time for online classes 4. Lack of social interactions "My child REALLY misses her teacher AND friends AND the classroom library. Otherwise, from what I see, she has shown signs of needing classroom norms/expectations of behavior while working that a teacher would provide structures for within the classroom (I.e., teachers card system, classroom rules about staying in assigned learning place, following teachers' directions, not interrupting, teacher's prize box)." 5. Lack of rigorous teaching materials"Poor study material, poor study presentations. Not easy to get in touch with the teacher to clear doubts." 6. Lack of students' knowledge"Not sure if my kids are getting everything done that they need and turning it in properly. Are they learning anything?" 7. Lack of teachers' support 8. Parents' anxiety about grades and moving to the next grade"My son does the minimum that is required of him to earn a good grade. Without a teacher in the room with him, he is not pushed and encouraged to do more, nor is he told if what he is doing is not enough until the assignment is graded. The teachers have been allowing him to redo assignments but being asked to do so frustrates and irritates him." 9. Excessively load of classwork and homework 10. Lack of support for special education students"My son has pulled out of language arts. The classwork still includes novels, but he was only given an audiobook, and listening is a weakness for him. Also, I feel like he is being given no accommodations by his regular ed teachers unless I push for them. He also has issues with language and communication, and he often misinterprets instructions." 11. Lack of hands-on activities 12. Lack of devices 13. Lack of communication from the teacher 14. Not being able to support all kids in the family"I'm a single mom with four kids, and I will be working full-time in the fall. Keeping up with distance learning with multiple school-age children will be challenging." 15. Dealing with a massive load of emails and links 16. Not all teachers are ready to teach online"I find the teachers, if not tech savvy, are giving work in a manner that is not easing work. For example, uploading pics of the textbook. Now the child has to type in the answers either on a blank document or download, edit to write answers, and then upload again." 17. Screen addiction"I have a philosophical dilemma with online learning for a first grader and a K4 student. Having learning for this age be necessarily tied to a device (computer, tablet, smartphone) goes against our parenting philosophy of no/minimal device time. Suddenly, we expect children to do the opposite of what we have worked hard to prevent. I do not want my child to have independence on devices at this age because I do not believe it is developmentally appropriate." These findings are supported by the research outcomes made by Dong et al. (2020), Drvodelic and Domović (2022), Mukhtar et al. (2020), Nenko et al. (2020), Sari and Nayır (2020), and Trzcińska-Król(2020). Lau and Lee (2021) found that most children faced difficulties completing online learning tasks due to limitations related to the home environment and a lack of learning interests. They could not complete the tasks independently, and their parents were dissatisfied with distance education. Agaton and Cueto (2021) emphasized that parents' challenges during the COVID closure involved dissatisfaction with the learning outcomes, financial difficulties, struggles related to technology availability and usage, as well as personal problems related to stress and health. Likewise, according to Al-Awidi and Al-Mughrabi (2022), parents believed that online learning failed due to (1) low students motivation, (2) poor electronic devices accessibility and internet connection, (3) family issues such as family size, economic status, and distance education culture. Nonetheless, Maksum et al. (2022) investigated twenty-five families (parents and their elementary school children) and found paradoxical perspectives about online education. While parents tended to view online learning negatively, their children perceived it positively. The research explained that parents and children had different attitudes and expectations toward online education. Advantages of Distance Learning The answers to the third research question about the advantages of distance learning were also evaluated using the thematic analysis method, and eleven themes emerged.

Conclusions The data analysis showed that half of the respondents acknowledged that their kids shared the same room while engaged in distance learning, and schools did not provide a home learning device. However, about 50 % of the parents felt like being supported by the schools and administrative staff and were ready to help their children. Parents presented some concerns related to distance learning, such as lack of motivation, social interactions, one-on-one support for special education students, teachers' readiness, gaps in knowledge, and challenges for children to stay focused. Distance learning advantages included flexibility in lesson participation and task completion, more family time, and forcing students to be responsible for their education. Positive family climate limited obstacles with distance learning (Pozzoli et al.,2022), and high-level teacher support and parental involvement were linked to high student emotional engagement (Yang et al., 2022). References Agaton, C. B., & Cueto, L. J. (2021). Learning at home: Parents' lived experiences on distance learning during covid-19 pandemic in the Philippines. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 10(3), 901-911. Al-Awidi, H. M., & Al-Mughrabi, A. M. (2022). Returning to schools after COVID-19: Identifying factors of distance learning failure in Jordan from parents' perspectives. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 12(4), e202232. Alharthi, M. (2023). Parental involvement in children's online education during COVID-19: A phenomenological study in Saudi Arabia. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(2), 345-359. Andarwulan, T., Fajri, T. A. A., & Damayanti, G. (2021). Elementary teachers' readiness toward the online learning policy in the New Normal Era during COVID-19. International Journal of Instruction, 14(3), 771-786. Asio, J. M. R., & A Bayucca, S. (2021). Spearheading education during the COVID-19 rife: Administrators' level of digital competence and schools' readiness on distance learning. Journal of Pedagogical Sociology and Psychology, 3(1), 19-26. Braun, V, & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. Calear, A. L., McCallum, S., Morse, A. R., Banfield, M., Gulliver, A., Cherbuin, N., ... & Batterham, P. J. (2022). Psychosocial impacts of home-schooling on parents and caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 119. Callahan, K., Rademacher, J. A., & Hildreth, B. L. (1998). The effect of parent participation in strategies to improve the homework performance of students who are at risk. Remedial and Special Education, 19(3), 131-141. Dong, C., Cao, S., & Li, H. (2020). Young children's online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Chinese parents' beliefs and attitudes. Children and youth services review, 118, 105440. Drvodelic, M., & Domović, V. (2022). Parents' opinions about their children's distance learning during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. CEPS Journal, 12(3), 221-241. Fan, X., & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students' academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational psychology review, 1-22. Francom, G. M., Lee, S. J., & Pinkney, H. (2021). Technologies, challenges, and needs of K-12 teachers in the transition to distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. TechTrends, 65(4), 589-601. Gonzalez-DeHass, A. (2016). Preparing 21st-century learners: Parent involvement strategies for encouraging students' self-regulated learning. Childhood Education, 92(6), 427-436 Haskins, A. R., & Jacobsen, W. C. (2017). Schools as surveilling institutions? Paternal incarceration, system avoidance, and parental involvement in schooling. American Sociological Review, 82(4), 657-684. Haslam, D. M., Tee, A., & Baker, S. (2017). The use of social media as a mechanism of social support in parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(7), 2026-2037. Lau, E. Y. H., & Lee, K. (2021). Parents' views on young children's distance learning and screen time during COVID-19 class suspension in Hong Kong. Early Education and Development, 32(6), 863-880. Lee, T. T. L. (2022). Leadership for inclusive online learning in public primary schools during COVID-19: A multiple case study in Hong Kong. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 17411432221135310. Li, Z., & Qiu, Z. (2018). How does family background affect children's educational achievement? Evidence from Contemporary China. The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 5(1), 1-21. Maksum, A., Wahyuni, E. N., Aziz, R., Hadi, S., & Susanto, D. (2022). Parents and children's paradoxical perceptions of online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic. Advances in Mobile Learning Educational Research, 2(2), 321-332. Mukhtar, K., Javed, K., Arooj, M., & Sethi, A. (2020). Advantages, limitations, and recommendations for online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic era. Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 36(COVID-19-S4), S27. Nenko, Y., Кybalna, N., & Snisarenko, Y. (2020). The COVID-19 distance learning: Insight from Ukrainian students. Revista Brasileira de Educação do Campo, 5, e8925-e8925. Nikolopoulou, K., & Kousloglou, M. (2022). Online teaching in COVID-19 pandemic: secondary school teachers' beliefs on teaching presence and school support. Education Sciences, 12(3), 216. Palero, M. A. G., & Mutya, R. C. (2022). Teacher's readiness towards online distance learning in science teaching in the new normal. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and applied research, 63(1), 132-154. Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Scrimin, S. (2022). Distance learning during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: The role of family, school, and individual factors. School Psychology, 37(2), 183. Samsonova, O. (2022). Teaching and learning during the pandemic closure: The higher education students' perspective. Current Research in Language, Literature, and Education Vol. 5, 59-72. Sari, T., & Nayır, F. (2020). Challenges in distance education during the (Covid-19) pandemic period. Qualitative Research in Education, 9(3), 328-360. Taddeo, C., & Barnes, A. (2016). The school website: Facilitating communication engagement and learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(2), 421-436. Tatlah, I. A., Masood, S., & Amin, M. (2019). Impact of parental expectations and students' academic self-concept on their academic achievements. Journal of Research & Reflections in Education (JRRE), 13(2). Tocalo, A. W. I. (2022). Listening to Filipino parents' voices during distance learning of their children amidst COVID-19. Education 3-13, 1-12. Trzcińska-Król, M. (2020). Students with special educational needs in the distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic–parents' opinions. Interdyscyplinarne Konteksty Pedagogiki Specjalnej, (29), 173-191. UNESCO. (2020). Global monitoring of school closures caused by COVID-19. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse Yang, Y., Liu, K., Li, M., & Li, S. (2022). Students' affective engagement, parental involvement, and teacher support in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey in China. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(sup1), S148-S164. Yang, Y., Liu, K., Li, M., & Li, S. (2022). Students' affective engagement, parental involvement, and teacher support in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey in China. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(sup1), S148-S164. Zhang, C., Du, J., Sun, L., & Ding, Y. (2018). Extending face-to-face interactions: understanding and developing an online teacher and family community. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46(3), 331-341

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

- Home

- About WVN

-

WVN Issues

- Vol. 1 No. 1 (Oct. 2017) >

- Vol. 2 No. 1 (Feb. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 2 (Jun. 2018) >

- Vol. 2 No. 3 (Oct. 2018) >

- Vol. 3 No. 1 (Feb. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 2 (Jun. 2019) >

- Vol. 3 No. 3 (Oct. 2019) >

- Vol. 4 No. 1 (Feb. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 2 (Jun. 2020) >

- Vol. 4 No. 3 (Oct. 2020) >

- Vol. 5 No. 1 (Feb. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 2 (Jun. 2021) >

- Vol. 5 No. 3 (Oct. 2021) >

- Vol. 6 No. 1 (Feb. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 2 (Jun. 2022) >

- Vol. 6 No. 3 (Oct. 2022) >

- Vol. 7 No. 1 (Feb. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 2 (Jun. 2023) >

- Vol. 7 No. 3 (Oct. 2023) >

- Vol. 8 No. 1 (Feb. 2024) >

-

Events

- CIES 2023, Feb. 14-22, Washington D.C., USA

- ICES 4th National Conference, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 20 June 2021

- 2022 Virtual Conference of CESHK, 18-19 March 2022

- ISCEST Nigeria 7th Annual International Conference, 30 Nov.-3 Dec. 2020

- 3rd WCCES Symposium (Virtually through Zoom) 25-27 Nov. 2020

- CESA 12th Biennial Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 26-28 Sept. 2020

- CESI 10th International Conference, New Delhi, India, 9-11 Dec. 2019

- SOMEC Forum, Mexico City, 13 Nov. 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Geneva, 14-15 Jan. 2019

- 54th EC Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 Jan. 2019

- XVII World Congress of Comparative Education Societies, Cancún, Mexico, 20-24 May 2019

- ISCEST Nigeria 5th Annual Conference, 3-6 Dec. 2018

- CESI 9th International Conference, Vadodara, India, 14-16 Dec. 2018

- ICES 3rd National Conference, Ben-Gurion University, Israel, 17 Jan. 2019

- WCCES Retreat & EC Meeting, Johannesburg, 20-21 June 2018

- WCCES Symposium, Johannesburg, 21-22 June 2018

- 5th IOCES International Conference, 21-22 June 2018

- International Research Symposium, Sonepat, India, 11-12 Dec. 2017

- WCCES Info Session & Launch of Online Course on Practicing Nonviolence at CIES, 29 March 2018

- WCCES Leadership Meeting at CIES, 28 March 2018

- 52nd EC Meeting of WCCES, France, 10-11 Oct. 2017

- UIA Round Table Asia Pacific, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 21-22 Sept. 2017

- Online Courses

RSS Feed

RSS Feed